Hery Paz – Fisuras – Review

HERY PAZ

Fisuras

Review

04

December, 2025

By: Khagan Aslanov

Photo: Artist,s concession

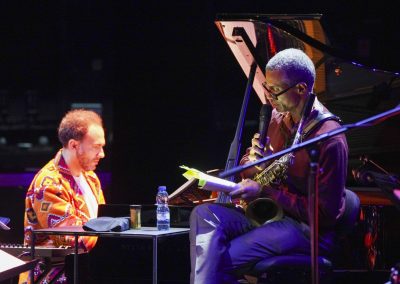

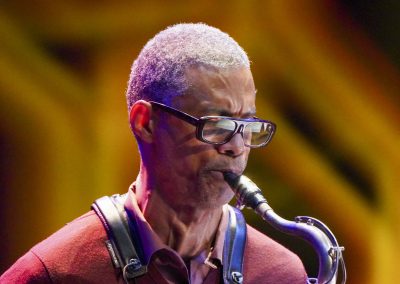

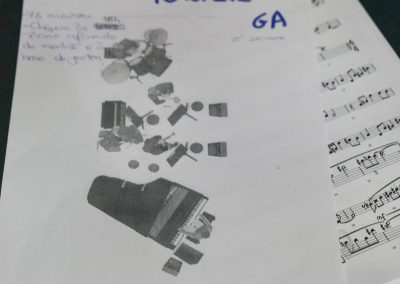

Review: “Fisuras”. Carimbo Porta- Jazz Label. (26 November 2025) Hery Paz, woodwinds, claves & Voice / Pedro Melo Alves, percussion / Joao Carlos Pinto Keyboard & Electronics / Demian Cabaud, bass, flute, bombo legüero / Maria Mónica, all live visual sorcery. Recorded Live at the Black Box /CIAJG. At the Guimarães jazz Festival.

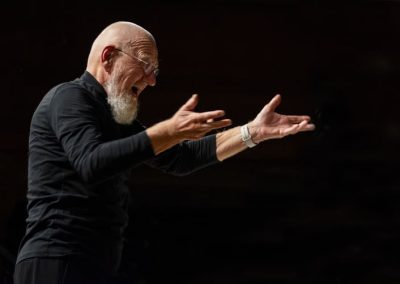

In some ways, Cuban-born, NY-based multi-instrumentalist Hery Paz is one of the only living postmodernists standing on firm ground. He composes, improvises, paints and writes, and though in most hands, this arrangement quickly crumbles into a hedged multi-pronged pursuit of mediocrity, what saves Paz from a similar fate is that in his craft, all these mediums function as load-bearing elements of a much larger whole. In that melee, his music may well act as an image, his painting as grammar, and his words as notation.

So it goes for his excellent new album Fisuras, an aural/optic undertaking that is intrinsically tied to language as a connective force. Recorded live last year, at the Guimarães Jazz Festival, the performance was an exercise in artistic syncretism, spoken and intoned poetry, visual “sorcery,” and acoustical and electronic improvisation.

Somewhat appropriately then, simple words may fail here. Fisuras was conceived as an all-consuming live experience, a group of artists in the middle of a multi-disciplinary ceremonial, and without Maria Mónica’s visual accompaniment, these pieces obviously lack a crucial aspect of their consumption. Thankfully, the poetry, throat-work and music on offer are so enthralling that even with a patch missing, a tremendous aesthetic effect is reached.

Through stuttering static, Paz ushers in the opener “Azul” on a short, emotive poem – ‘Blue. The legs devoured by blue. The soul parched. The ropes rotting. The beam ruined with age.’

What follows is a Mingus-esque intro, made dense with brawny bass-work, chaotic percussion and atonal sax, while a hanging curtain of squawking electronics lays the backdrop. About four minutes in, the instruments pull back, and the piece begins a short decay into claves and twitching percussive synthetic pulsing. Then the group descends again. At the next break, Joao João Carlos Pinto plays a short measure of kitschy keys that bring to mind 70’s giallo scores, and then “Azul” begins a drift into an unsettled ambient space, intermittently snapped by sharp, collective interplay.

As the piece winds down in a fit of Demian Cabaud’s bowed bass, Paz repeats the poem, adding as an epilogue ‘Into the wet earth, I bury hunger, one bone after another, and another, and another…’

It’s a wholly consuming 14 minutes, a piece that contracts and expands continuously with fluid identity, full of systolic fluctuations, nowhere and everywhere all at once.

From there, Fisuras runs the gamut of free jazz mastery. On the supremely patient “Solo Por Hoy,” over another spoken ode to melancholy and dread, Paz’ saxophone takes on a hanging atmospheric tone, part Coltrane’s dolour, part Brotzmann’s desolate anarchy. The frenetically beautiful “Golpes” is a display of percussionist Pedro Melo Alves’ kit skills – a pyrotechnical show of high-strung dynamics and irregular phrasing, he creates a feral foil to the piece’s glitchy electronic procession. On repeat listens, more and more nuance emerges from every piece, a thousand pointillist details that merge into a heart-rending sum.

Even to the untrained ear, the tightly-plaited interplay and knowing hands that guide Fisuras make the album a wonder to hear. This performance represents what is so incredible about improvised music. A group of virtuosos reaching internally, for meaning and sound, and then thrusting them outward into the audience, to create a perfect aesthetic moment.