Tigran Hamasyan Interview Jazz en el Auditorio (CNDM)

Tigran Hamasyan Interview

Jazz en el Auditorio (CNDM)

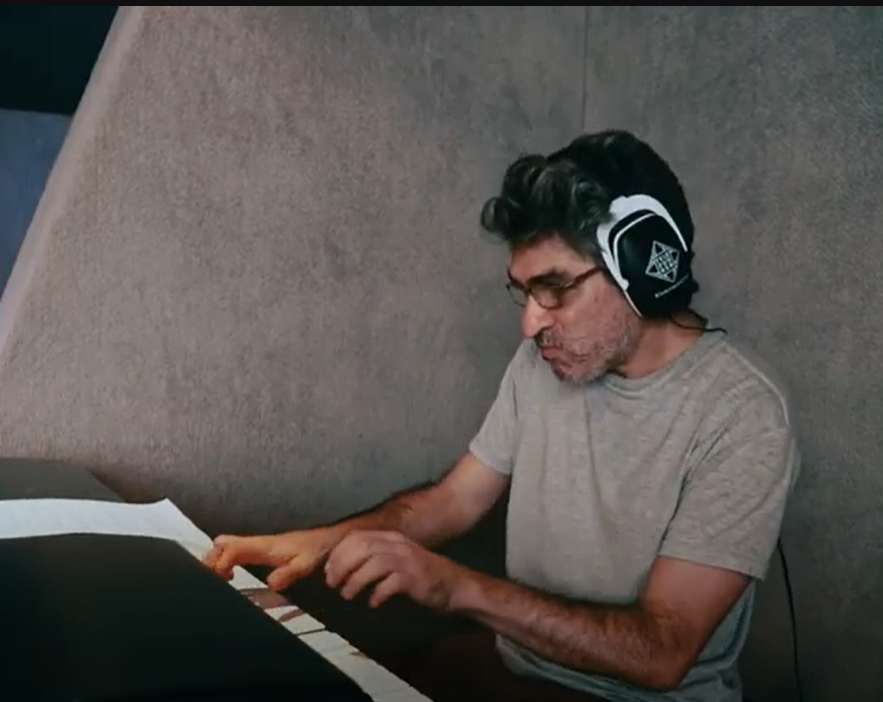

On March sixteenth I was honored to interview one of the greatest piano players of our time. After playing in Paris and as part of his tour promoting his latest album StandArt, Tigran Hamasyan came to Madrid on 18th of March with bassist Rick Rosato and drummer Jonathan Piston to offer a concert at Auditorio Nacional de Música, in the framework of the Jazz cycle of the Centro Nacional de Difusión Musical (CNDM), playing his own vision of jazz standards through outstanding and personal arrangements in a virtuosistic, intense and exuberant approach.

The Armenian pianist carries deep sensibility and a personal understanding of jazz, Armenian folk and rock music among others. Hamasyan is, indeed, one of the main piano references of the international jazz scene nowadays.

In&OutJazz: Dear Tigran, thank you so much for accepting this interview and for sharing with us some of your time. We are very excited to ask you some questions related to your musical world.

You have always connected your Armenian roots to jazz, and so are a big inspiration for many musicians but you have always followed your true path. Your music is intense, powerful and it has a characteristic beautiful rudeness in it, full of energy and many different worlds in it, inside jazz. How do you relate nowadays with all these different musical worlds that are part of your music?

Tigran Hamasyan: Well, it is a very good question, you have to have an immense focus these days. I feel that every time in history has its own challenges and, at the present moment, we need a direction of where we are going because otherwise you get easily lost, due to the amount of information and distractions we have every second. I feel that these distractions are on a much bigger stage than for example 150 years ago. I believe it is important to filter out all the meaningless stuff of your life; music as well, I am not only talking about social media.

Up until the industrialization we had two kinds of music, with their branches of course; they were religious music and folk music, with obviously different kinds of it inside these two. They were made, played or sung for specific times, festivities or processes, like for example making bread or working times, like work songs or shepherd songs… or lullabies, something almost sacred, meaningful in a way.

Nowadays, you take a taxi or enter a Cafe… and there is music wherever you go and this music has nothing to do with the present moment of your day or with the time you live in or simply to what your head is and where your thoughts are. The thing is, you cannot avoid music because it is everywhere, and therefore the value of music has gone down so much. Also, in most of the places you go, you are almost forced to hear terrible music that you do not want to listen to. What I’m saying is just to take a picture of the difference of each time, so now you need a lot of focus to filter everything out and make the decision of what to listen to. Back in the days this could happen but much less than now.

In&OutJazz: So what do you do to stay focused and keep your attention?

Tigran Hamasyan: I carry my headphones all the time to try to not be forced to listen to what I do not want to listen to, or to just make it lower. I like any kind of music, any style, but I like specific things in that style, for example, I love metal but not any kind, I like Meshuggah, Tool…but not all bands of metal and all types of it.

In&OutJazz: Have you constantly got to be focused and clear what your identity is, or did it appear at some point?

Tigran Hamasyan: You know what you want to work on in this instant or period of time, right now I am working in this thing and I know that I have to work on this thing, so this will lead to another place and maybe you write a song, and maybe then you do a project, and this will bring you somewhere else… and so on. Maybe one day I record myself and I have different kinds of recordings. I know the process I did and why I came here, I cannot predict where I am going, the only thing I can do is to work on myself and keep up the direction of where do I want to go now, constantly learn from the past and develop, this is the road… it’s a process it’s just to be self-realizing. You have to realize what you are doing and then work and work.

In&OutJazz: Do you have time to work on tour?

Tigran Hamasyan: Yes, you make time, there is always time actually if you want to practice. Those who say: “

I don’t have time, I am too tired…” are just telling an excuse. You make time, if it’s your priority it is possible, it just has to be on top of your priority list.

In&OutJazz: Do you still listen to Tool and Meshuggah in your everyday life? Who do you find yourself listening to lately?

Tigran Hamasyan: Yeah, I go to periods, now for example I am more into jazz and classical music but then one month I am into electronica or rock or whatever. Each time I listen to something interesting I try to get it deeper and understand what is going on. Sometimes it influences my music and inspires me to explore, so I guess this is the positive side to excessive music that you can access instantly.

In&OutJazz: Do you feel that something has changed nowadays in relation to how music has been created?

Tigran Hamasyan: Suddenly it is possible to do music without years of development and this has changed everything. There is a lot of information and a lot of incredible things happening and this forces me to know exactly what I am doing and to really work on my stuff on myself, to really be bringing my level up every time I do a project or a performance, because I am competing all the time to the entire world online, in a way.

In&OutJazz: Do you feel you have to be competing to the levels of what other music and genres are doing also?

Tigran Hamasyan: Yes! That is exactly what is happening and there is incredible music out there, so you have to be always working on yourself to get better. I would do it anyways but it makes even more sense now because there is so much information.

In&OutJazz: Do you like the process of pushing yourself to get better?

Tigran Hamasyan: No, I do not at all, I love discovering and looking for things. My parents used to force me to go outside and play concerts when I was a kid because I practiced too much. To practice is not a problem for me, I like practicing and focusing on what I want to do and make music, the problem is to have to go to social media and marketing. Now, I do not do it personally, someone does it for me and talks to record companies and so, I feel fortunate about it. We live in a period in which record companies ask you first how many followers you have and then which music you do.

In&OutJazz: Let’s talk about your journey from World Passion to StandArt. Which evolution do you think you and your music have had from your first project to your latest?

Tigran Hamasyan: I am trying to be as much aware as possible but I would say compositionally things have developed a lot. Nevertheless, I am the type of guy who always thinks that things are bad and I am degrading so it is difficult to have an objective point of view.

In&OutJazz: After all this time, how is your relationship with piano?

Tigran Hamasyan: I feel great, it is a challenge and joy, suffering and enjoying at the same time. It cannot be only joy, there must also be suffering because that is how you discover new things, you get out of your comfort zone, and you develop. I take the challenge every day, the main thing is to know what you want to develop and the direction you want to have, especially as an improviser it is important to remember what you play and constantly work on a daily basis of what your vision is.

In&OutJazz: How do you work on your vision? Where do you focus your attention?

Tigran Hamasyan: It depends on the moment. Now, I am working on letting things go out of control, working on specific harmonic vision and on dynamics. When you really improvise and let things go and things are flowing it’s easy to get into a habit, like: “I play this and that”, so you always get into the same thing, a collection of habits and you repeat yourself. When we are on tour we play arrangements of jazz standards, for example in the last soundcheck I did not like what I was playing.

Improvising now with Rick Rosato and Jonathan Piston is being a great source of inspiration to find and explore all these ways. It’s like what you are doing and then what you are doing in this band. Ensemble and individual working.

In&OutJazz: In a way, StandArt is very traditional, and probably the most traditional coming from you. How did the idea of Standard come across and why did you choose jazz standards and not your own creations as before?

Tigran Hamasyan: I have been playing standards since I was ten maybe, so I always knew that someday I would give a homage to where my roots begin, because I started with jazz and rock. The reason that I chose jazz is because I love improvising. Even when I tried to make some rock songs I did not like to write things down, I loved to make them up.

In&OutJazz: Do your compositions come from improvisation?

Tigran Hamasyan: Yes, they always start initially with improvisation. I always had the realization that I wanted to do jazz standard at a moment. I got to a point where I could put all the ideas that I have developed over the years into the jazz standards, which contain great beautiful melodies.

There are specific songs to which I have a specific emotional connection and memories, these songs have a lot of meaning for me and that’s why I wanted to do the project. I loved putting my rhythmic and harmonic ideas on the standards, they are like folk music and you never get tired and stop exploring folk music.

In&OutJazz: Why did you choose StandArt as your album’s name?

Tigran Hamasyan: I named the album StandArt because sometimes we feel that there are just standards that are there and we forget that they are also forms of art, some of them a high level of art, really deep with melodies that are timeless.

I have a friend, Gaguik Martirosyan, who is an Armenian painter and paints Parisian scenes, like different outside locations, cars, geometrical forms, etc. He watches the outside world and he paints it in his own way, with a tremendous personal way. This was also a huge influence on me and an inspiration to call this StandArt, Gaguik Martirosyan and I are basically doing the same thing, looking at things that we do everyday that became standards but revisiting and reimagining them.

In&OutJazz: In the album you recorded and made collaborations with amazing artists like Ambrose Akinmusire, Joshua Redman or Mark Turner. Also, this record is based on a trio with Matt Brewer and Justin Brown. Why did you choose both the formation and the musicians involved in the project?

Tigran Hamasyan: Well, I knew Justin since college years, and I played in some L.A. jam sessions with him. Also, I know Ambrose Akinmusire because he was studying in the same facilities where I went in L.A. I guess this is the California connection. When I wanted to do this record of standards, Justin Brown came to my mind. I always followed what he was doing with Ambrose Akinmusire and Thundercat. Justin has incredible energy and ears; it is comfortable to play with him because he would never play something that distracts you but at the same time, he is constantly providing flowing immense energy that comes directly at you. But this energy is not getting in the way and is distracting. I must be faceless and say that I have a good intuition for finding members for projects. If I listen to a person and I feel the energy I know instantly if it’s going to match. This, I guess, was the same that happened with Matt Brewer and the rest of components of StandArt.

In&OutJazz: On this occasion you are touring and coming to Madrid with Rick Rosato and Jonathan Piston, how is it to work with them?

Tigran Hamasyan: They both are unbelievable players, with amazing ears, it’s working fine. They are pushing me to create and think differently, which I find great.

In&OutJazz: You said previously in your life that Vahagn Hayrapetyan, who was a student of Barry Harris, came to Armenia and changed your life, showing and teaching you jazz. Did you have a mentor in Armenian music who introduced you to this folk tradition? And, how did you get in contact with this music?

Tigran Hamasyan: Actually, I did not have a teacher of Armenian folk music or any other folk music. I discovered it through jazz, through musicians like Jan Garbarek, John Coltrane, Keith Jarrett… I heard that these people were using a vocabulary that is different from bebop, like, for example, Jan Garbarek. When I listened to him for the first time I thought this is very nice but is outside my comfort zone, it’s not inside bebop vocabulary, he has folk music influences and much more. So I decided to check folk music vocabulary and I realized that I have my own tradition as well.

Then I got a book of Armenian folk compositions called ¨Armenian folk composition¨, which is the main book that is studied in the conservatory when you go to the folk faculty. I transcribed a lot of Armenian folk music, apart from solos of Coltrane and Chick Corea. That is how I got out of bebop and I discovered other music because I realized that I cannot treat folk music with bebop harmonies, this is not possible, so I had to find another solution, and this brought me to different habits and ways of using harmonies. The world of post-bop, with more open structures, and world music, suddenly made sense to me, classical music like Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Ravel, Debussy, or Armenian composers.

In&OutJazz: The mixture between Armenian folk music, jazz and rock happened through time in an unexpected way, as a natural consequence of your development or was it something you were looking for?

Tigran Hamasyan: One thing I realized was that to be able to compose and improvise over folk music, first, I have to make it a part of my music vocabulary. Not every song that I compose has an Armenian influence of course, I have my way to decide if a song has an Armenian influence or not. I realized that the only thing I can do to improvise folk music is to find information about the harmony and melodies inside the folk music and not outside sources. I could understand outside sources and have knowledge of outside sources, but still have to go to the folk melody itself and find harmonies and create harmonies based on that mode in which the folk song is written. And perhaps find innovative new ways of dealing with the mode and expanding it. In other words, it cannot be nice jazz that you put above the folk song and call that an arrangement. You need a deeper thought on it and need years to develop this kind of relation with folk music. You need to know the folk music in a deep manner, in a way in which when you compose you are actually creating new folk music. It’s like flamenco culture, you learn it and you live it and then you compose in that world. You have to be in the tradition and then you start speaking that language. Afterwards you start writing your own.

In&OutJazz: Do you also play with Armenian folk musicians?

Tigran Hamasyan: Yes, I do, but I try to limit myself as I like playing Armenian folk music but I don’t like doing projects with Armenian folk musicians because I don’t want to use that sound, as there are so many musicians that are just bringing folk instruments. It instantly sounds like ‘cliché’ but, to me it’s important to pay Armenian music but play with modern instruments.

In&OutJazz: Which is the next project you have in mind?

Tigran Hamasyan: There is something huge coming next year, actually my most ambitious project, it’s going to be intense… so get ready!

In&OutJazz: You are one of the main references, many young musicians listen to your music when they approach and learn jazz, would you give any advice to young generations?

Tigran Hamasyan: I would tell them to stay focused on what you want to do and maintain yourself on it. Think in terms of the vision that you have, thinking can be negative and too much is bad, but it is important to know which direction you are taking, and to stay true to that, because there are lots of distractions. Do not spend time on stupid Facebook or Instagram, and spend that time thinking about projects, listening and analyzing music, and practicing, practicing and practicing. If you have the talent and you love music more than anything else then you have to show that you love it more than anything else… and the way you show it is by practicing.

In&OutJazz: Thanks for your time. It has been a pleasure having the chance to talk with you today.