Enjoy Jazz Heidelberg 2025

ENJOY JAZZ

Heidelberg 2025

24

November, 2025

Text: Pedro Andrade

Photos: © Christian Gaier; Frank Shindelbeck; Kati Nowicki; Arpan Joost

Enjoy Jazz Reaches Its 27th Edition: Three days are enough to understand its greatness

Attending Enjoy Jazz this year meant stepping into a space where music doesn’t just sound — it thinks. This is no coincidence: behind that artistic architecture is the hand of Rainer Kern, a figure who understands jazz as a tool for cultural transformation. A scientist by training, cultural diplomat, and founder of the festival in 1999, Kern has turned Enjoy Jazz into more than an event: it is a platform where memory, politics, and experimentation intersect, capable of sparking social dialogue that extends far beyond the stage. The festival, held from October 2 to November 8 and featuring over 50 performances, is an ambitious undertaking sustained only by a strong network of coordination and trust.

This institutional and private framework supporting the festival should not be taken for granted. It is a tangible demonstration of what can be achieved when institutions, businesses, and civil society understand culture as an investment in sensitivity, education, and cohesion. Enjoy Jazz confirms that when a community commits to the arts, it does so not merely for entertainment but for expansion: to learn, to know itself, to expose itself to new stimuli that broaden perception.

Within this context, the first major impact came from Dee Dee Bridgewater and her program “We Exist,” an artistic gesture that is also a political statement. Bridgewater shaped the repertoire with a presence that transcends the category of “great vocalist”: she acted as an active witness to a legacy that reaches back to Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln, yet is being urgently rewritten today. Her voice remains a vessel of memory and resistance, capable of sustaining a discourse that embraces both historical pain and communal strength. At her side, Carmen Staff anchored the piano with an admirable balance of leadership and sensitivity; Rosa Brunello brought a double bass full of intention, firm and attentive to space; and Julie Saury, on drums, contributed an elegant, sober, almost narrative pulse that rounded out a profoundly meaningful ensemble. The exclusively female lineup was not merely an aesthetic choice—it was a declaration of independence in a circuit still burdened by patriarchal inertia. At the BASF auditorium, filled to every seat I could see, the concert resonated like a conversation between generations: the critical tradition of jazz updated without nostalgia, delivered with an ethical clarity that one can only appreciate.

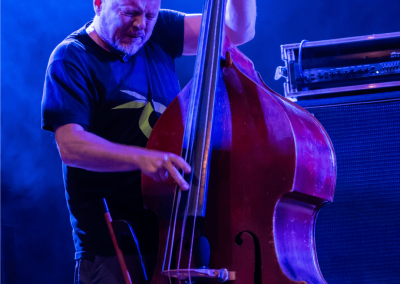

With The Young Mothers the following day, the terrain changed completely. There, structure revealed itself within apparent devastation. What may seem chaotic is crafted with meticulous design: tensions that accumulate, explosions that morph into new forms, energy that transforms rather than dissipates. Ingebrigt Håker Flaten—whom I had the chance to interview—leads the sextet with an almost physical intuition, sustaining a project integrating free jazz, hip-hop, noise, hardcore, and groove as if all belonged to the same ancestral code. Jawwaad Taylor opened poetic fissures within the turbulence; Horne pushed the guitar into abrasive zones; Rosaly and González generated a rhythmic topography that was unpredictable yet rigorous. In the Betriebswerk, that former railway workshop with its raw industrial aesthetic, the music took on an almost ritualistic power. It was a concert for listeners willing to lower their defenses: those who did found a fierce coherence within the excess.

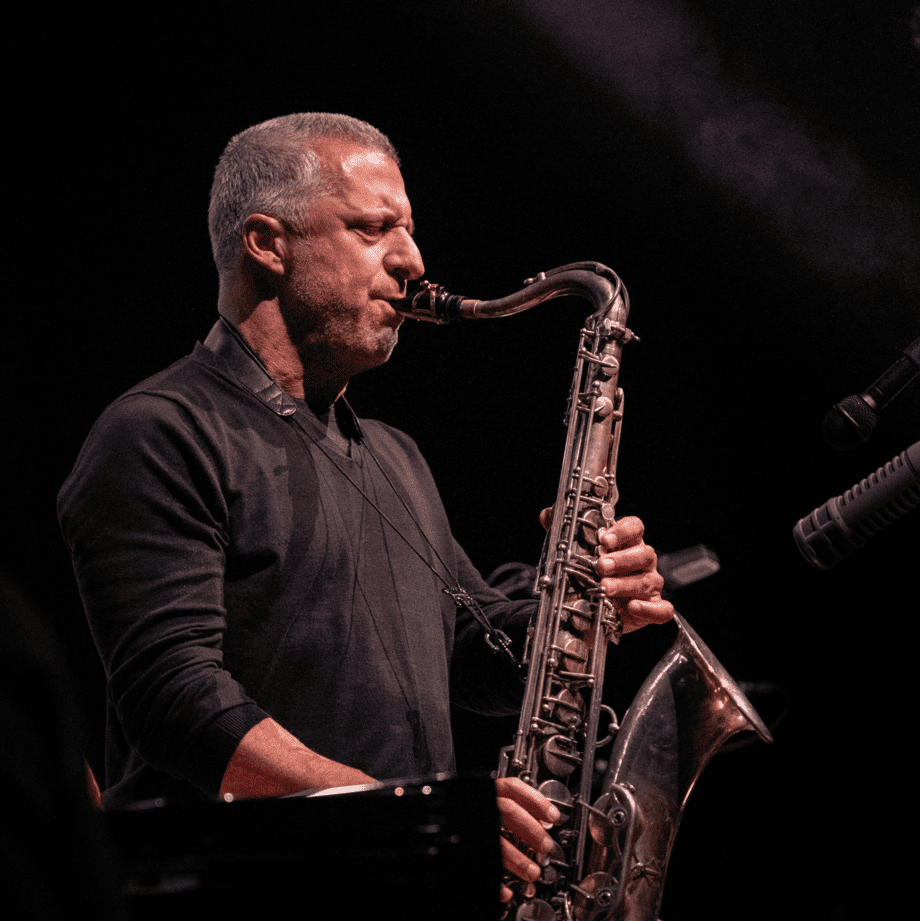

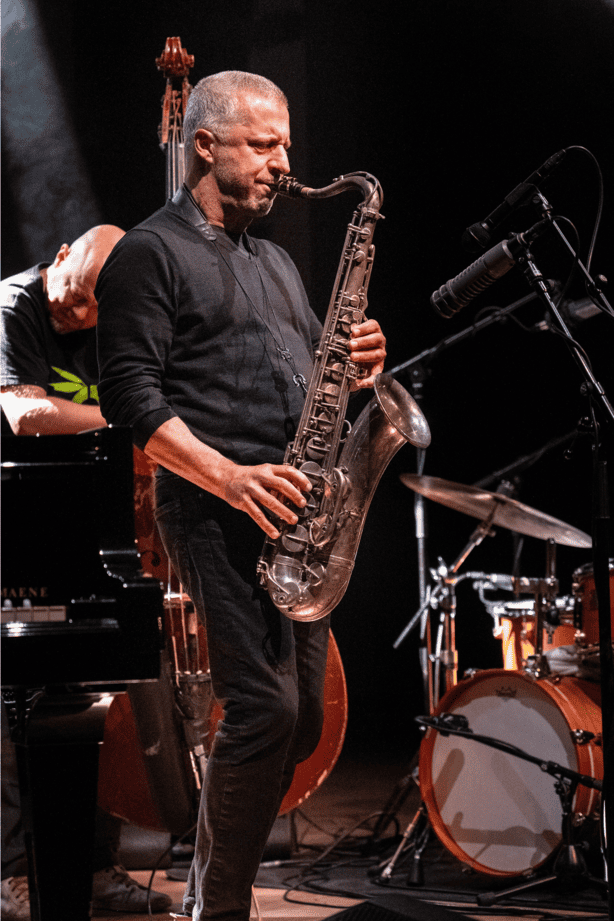

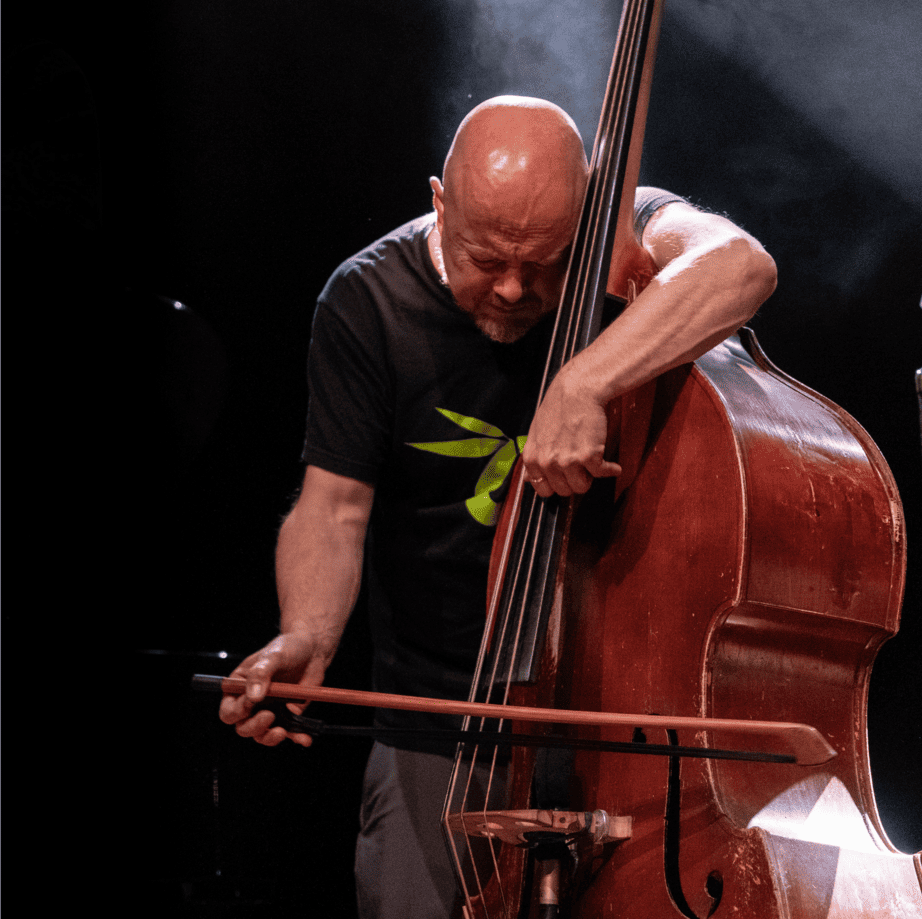

On Sunday, November 2, in a morning slot, I attended the first of two performances by Shai Maestro — a concert that offered respite, yes, but never intellectual rest. Maestro plays with a disarming sincerity: every phrase seems to search for an inner truth rather than a technical solution. His trajectory — from classical piano to the revelation of Jarrett, from competitions to his refusal to enter Berklee, from studying with Avishai Cohen to his consolidation with ECM — is evident in the way he breathes music, how he lets ideas articulate themselves with an almost organic naturalness.

Jorge Roeder provided a warm, rounded double bass sound, full of intention; Ofri Nehemya offered drumming of extraordinary sensitivity, attentive to even the slightest detail; and Agdy Lehavi added layers of synthesizer that expanded the quartet’s emotional universe without displacing its acoustic core. In a world where music is cleaned, edited, and quantized until it loses its soul, hearing Shai Maestro is a reminder that the human — the imperfect, the uncertain, the revealing — remains the true substance of jazz.

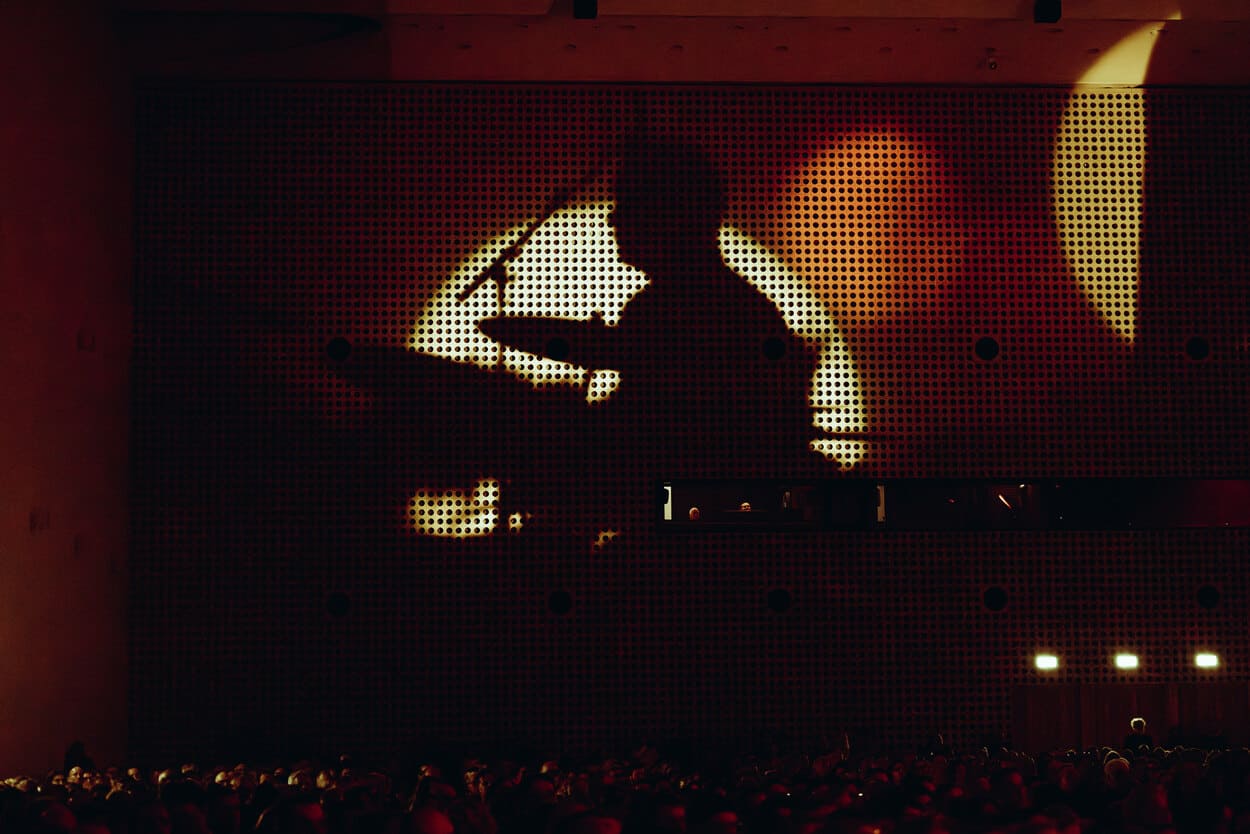

That same day, in the late afternoon and evening, I attended a concert that was entirely new to me. Kruder & Dorfmeister activated memories of an era when electronic music became an emotional and urban language. Their return with K&D Sessions Live is not merely nostalgia but a reaffirmation of an aesthetic that shaped the sensibility of the 1990s. Their blend of downbeat, dub, trip-hop, and nu-jazz remains elegant, atmospheric, crafted with timbral precision. It is not the kind of risk I personally seek in a festival concert, but the influence and magnetism they exert on their audience — their audience — is undeniable; the crowd lived the night as a generational rite, giving themselves over to an aesthetic that appeals not to euphoria but to immersion. There were moments of diffuse, almost cinematic beauty.

Three days at Enjoy Jazz were enough to confirm that the festival is not just a brilliant program: it is a cultural ecosystem where music is lived as thought and as action. I am deeply grateful for the invitation and the care received, especially thanks to the impeccable work of Michael Braun. At a time when culture needs arguments, support, and vision, Enjoy Jazz shows that coordination, commitment, and collective effort can turn a territory into a true laboratory of sensitivity. Where music is listened to in order to understand the world, society becomes a little more lucid.