Aziza

Aziza

Lionel Loueke – Chris Potter – Dave Holland – Eric Harland

10

ENERO, 2022

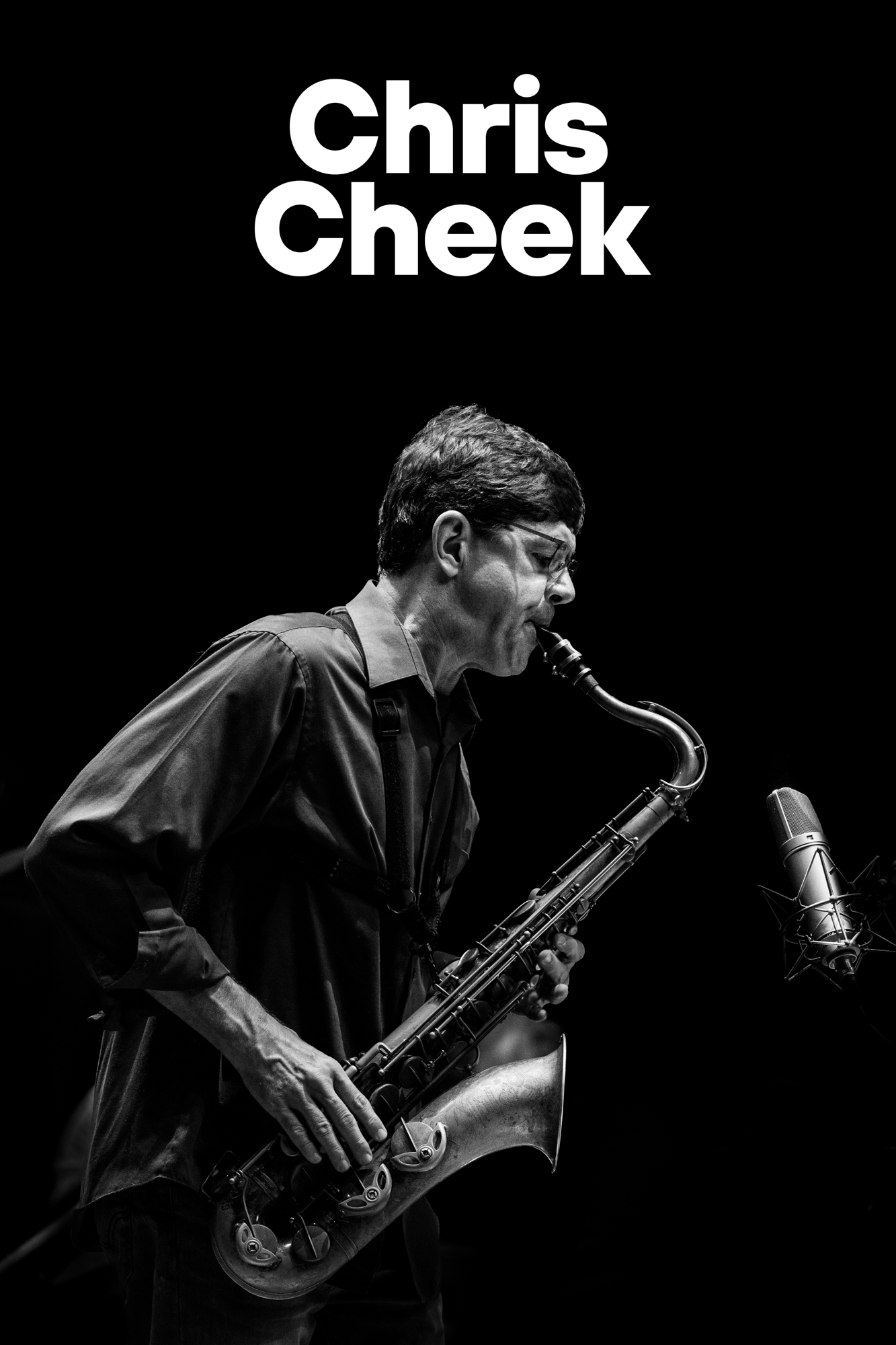

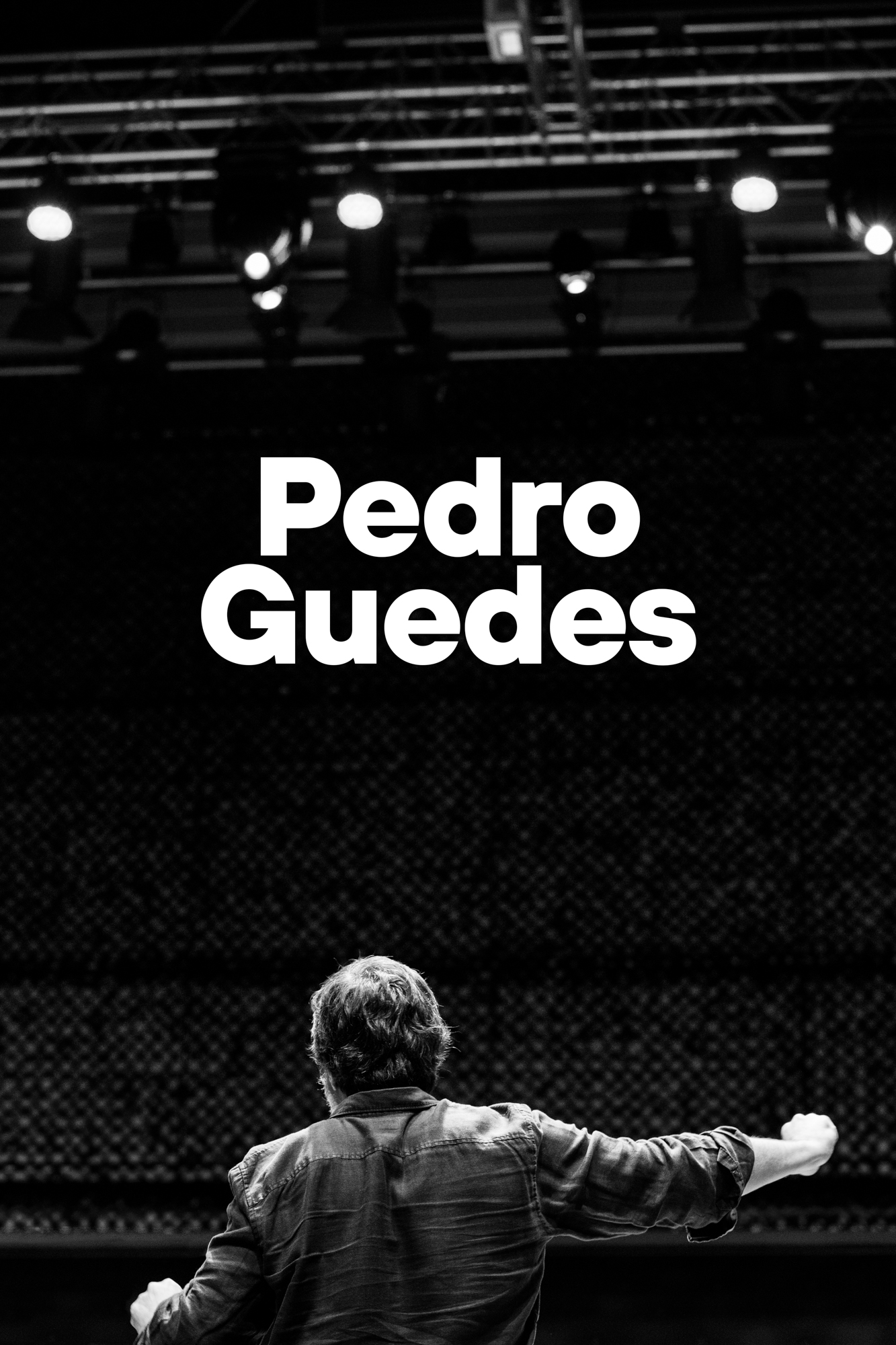

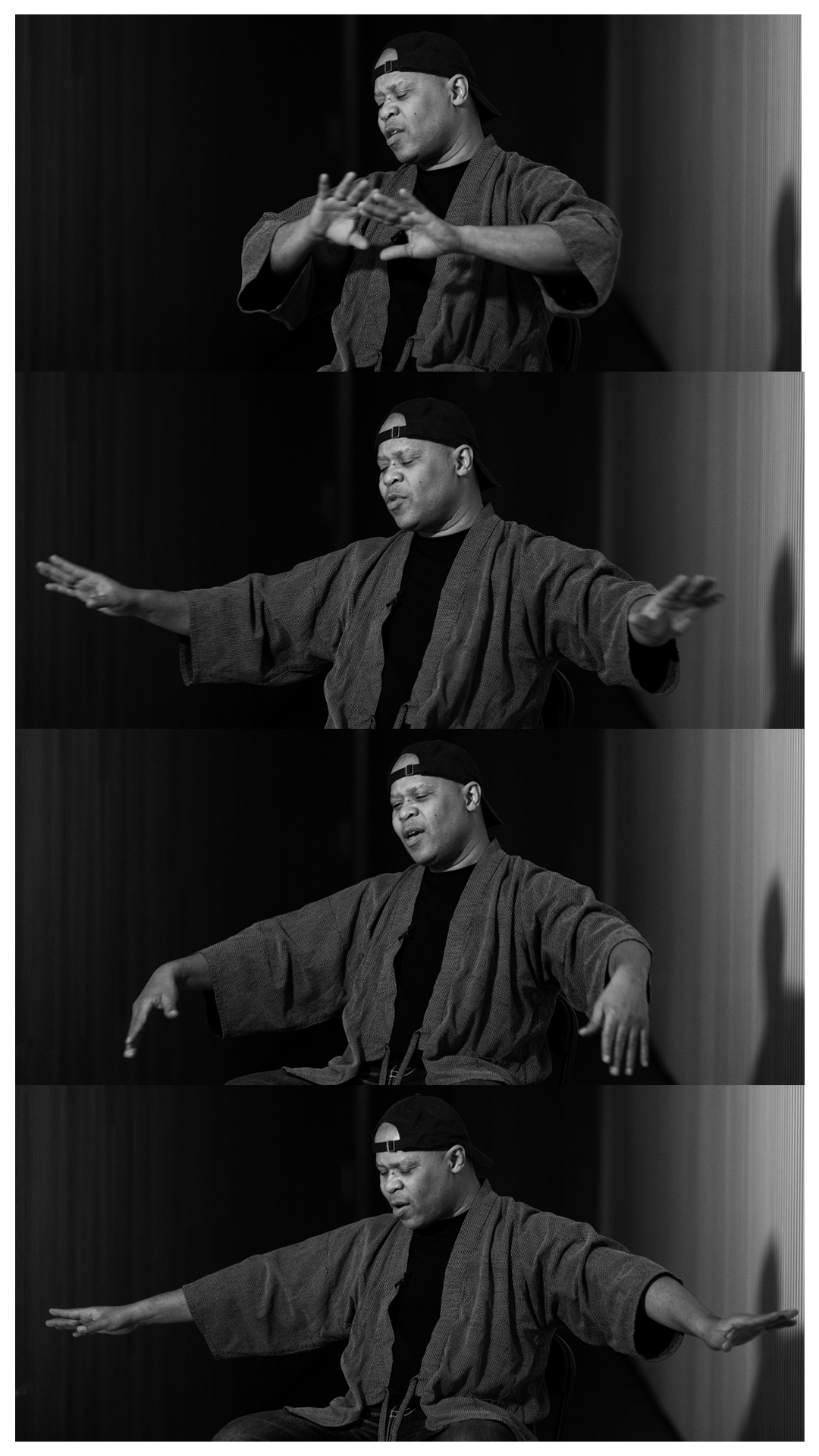

Lionel Loueke, guitarra y voz/ Chris Potter, saxofones/ Dave Holland, contrabajo/ Eric Harland, batería. Villanos del Jazz. Teatro Pavón. Festival de Jazz de Madrid 2022.

Texto: Manuel Borraz

Fotografía: Fernando Tribiño

El pasado 8 de noviembre tuve el placer de asistir al concierto de cuatro leyendas vivas del jazz, Lionel Loueke (guitarra y voz), Chris Potter (saxofones), Dave Holland (contrabajo) y Eric Harland (batería) organizado por Villanos del Jazz en el Teatro Pavón bajo el marco del Festival de Jazz de Madrid 2022.

Contadas son las ocasiones en los que grandes instrumentistas e improvisadores se juntan para conformar un jazz en cuyo desarrollo no relate ni haga apología de las altas técnicas que disponen y revelar así un lucimiento personal, sino en el que su cometido sea el de prestar cada una de sus destrezas individuales al servicio y beneficio del proyecto común, creando un espacio colectivo en el que expresarse y aportar a la propuesta en su totalidad, generando la esperada unidad de banda. Aziza representa este caso.

Aziza es el nombre de este conjunto y proviene de una canción escrita por Lionel Loueke llamada ¨Aziza Dance¨. En Benín, África, lugar del que procede Loueke, el término «aziza» hace referencia a una sobrenatural raza de habitantes del bosque que cuentan con la capacidad de dar consejo espiritual y práctico. Dicha sabiduría queda reflejada en la interacción de sus componentes y fue recogida y elaborada en un álbum producido por Dave Holland, grabado el 14 de octubre de 2016 y editado por el propio sello de Dave Holland, Dare2 Records Label. En el álbum, tal es el reparto equitativo de cada uno de los músicos que constituyen este supergrupo, que cada uno de estos compuso dos temas para el proyecto de los ocho resultantes, conformando un trabajo discográfico con una identidad colectiva.

Dave Holland ha estado llevando a la música por senderos y direcciones tremendamente interesantes e impredecibles desde 1960. En esta ocasión, Aziza se desenvuelve en un terreno que permite contribuir con libertad el talento e identidad propia de cada miembro, creando un carácter único y expresivo en la mezcla total. Por supuesto y como era de esperar, la velada trajo consigo grandes solos por parte de los cuatro músicos, un sinfín de momentos únicos y un gran despliegue de posibilidades sonoras, demostrando la riqueza de lenguaje por parte de estas auténticas bestias del jazz. Cabe destacar la presencia de Loueke en el proyecto, con una creatividad incomparable, una alta conexión y sensibilidad musical con su tierra natal, una gran versatilidad idiomática y una amplitud sónica y relacional fuera de lo habitual.

En conjunto, el directo de Aziza es rompedor, salvaje y vibrante, mantiene y juega con la atención del oyente, los cuatro músicos vuelan y se lanzan al vacío, son todo espectáculo y carácter. Ya son múltiples las ocasiones en las que esta banda ha encarado este proyecto en directo, pero todavía no podemos predecir qué le deparará el futuro. Esperamos que no se quede en un encuentro fortuito entre grandes figuras del jazz, sino que expanda su lenguaje a nuevos imaginarios, revelándonos así todas las posibilidades que sabemos que aguarda.