Lucille Moussalli – A Serious Prankster

.

.

.

.

Lucille Moussalli

A Serious Prankster

05

March, 2026

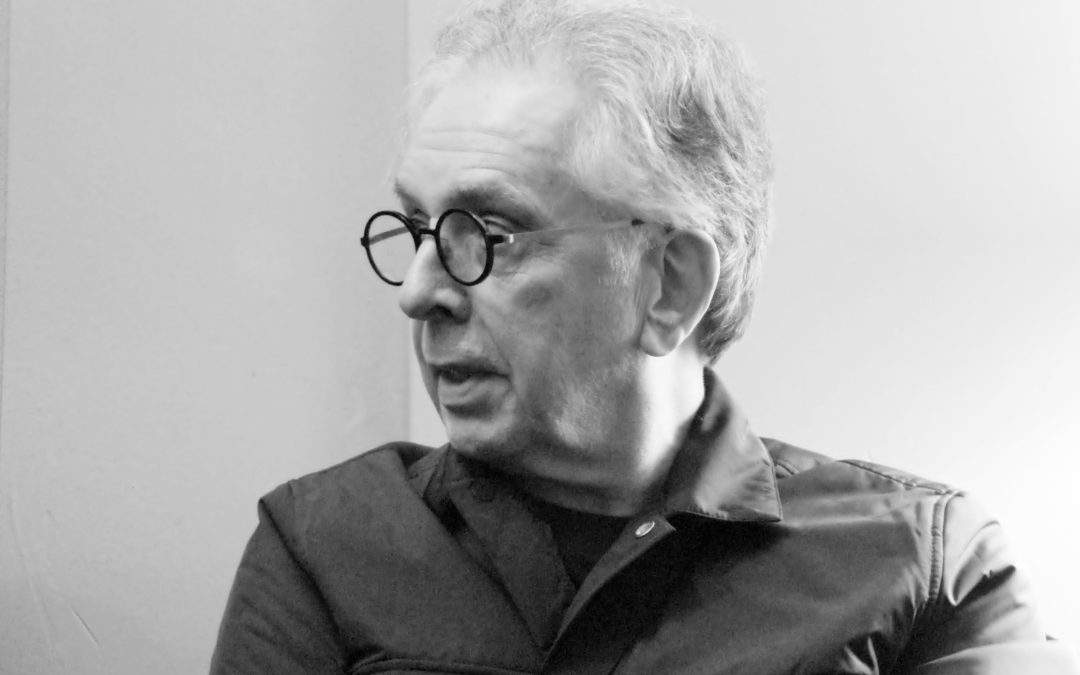

Text: Matthieu Jouan

Photos: Citizen Jazz

Citizen Jazz/ #IWD2026 | WomenToTheForce | A Serious Prankster

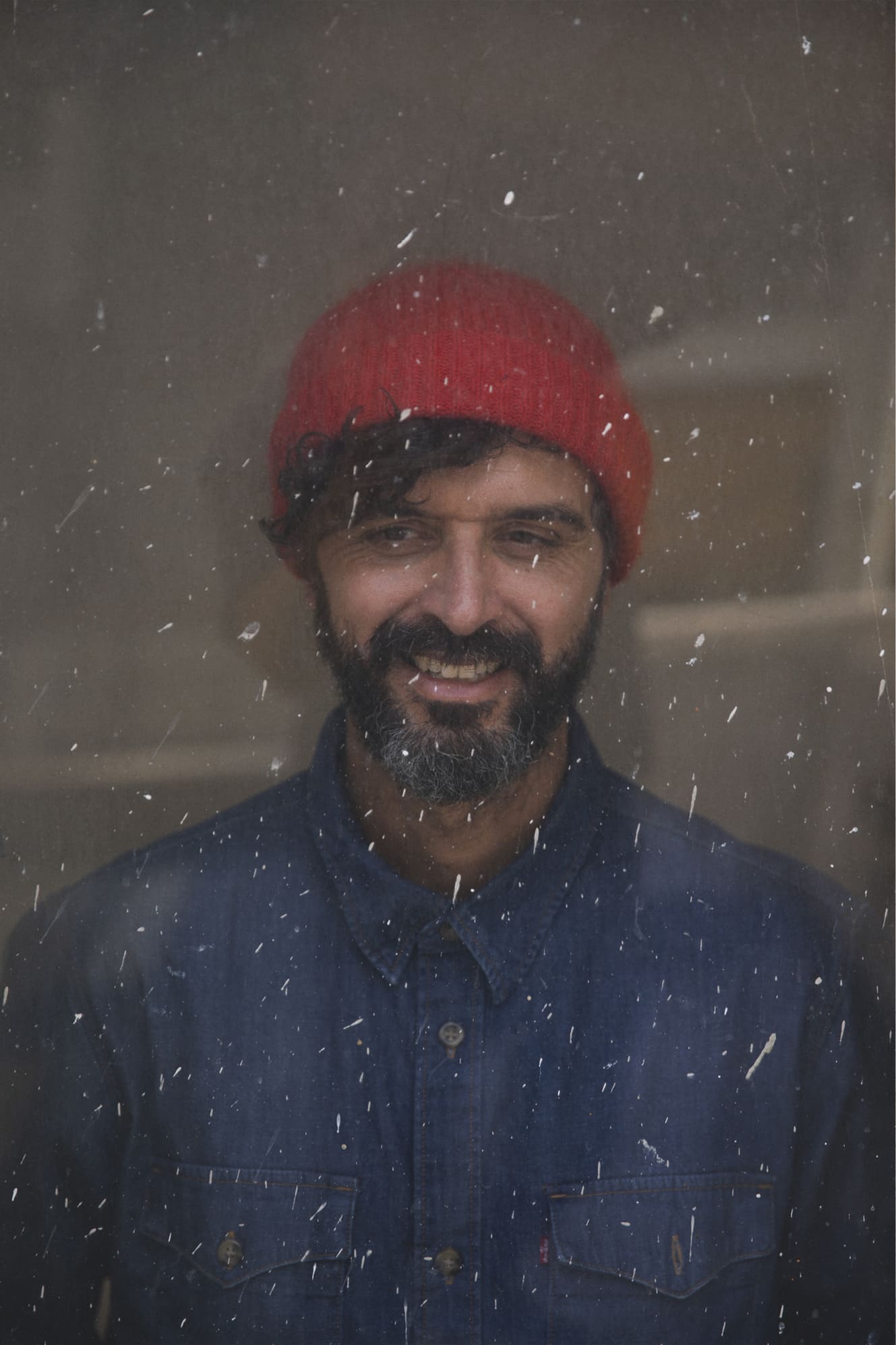

Portrait of a young trumpeter and violinist in full artistic bloom

Born in Vendée in a family where music and instruments have always been important, Lucille Moussalli first turned to the violin. An instruction at the music school between the ages of 6 and 14, complemented by a trumpet class starting at the age of 9. Then she entered high school in Nantes in the theater, music, and dance section, completed her studies, and joined the Conservatory in Paris in 2023.

She has always been surrounded by music: “My maternal grandfather played (and still plays) an important role in my musical education, he would play many musical instruments for me when I was just a few months old, and he was the one who taught me the basic basics of the violin”.

You got your start in Nantes, what do you think of this jazz scene?

Each city is an ecosystem defined by the individuals that compose it. Since my arrival in Paris, I feel fulfilled. I am fortunate to have met the people I play with today, and I appreciate the privilege of living in a large city bustling with so many cultural activities. Nantes is special. I feel good when I go back there, it’s where I had my first jams and it’s always nice to reconnect with the people I played standards with. You need to find out about the artists and venues in Nantes and go see them.

You need to come and support them because the Pays de la Loire region has suffered drastic budget cuts (73% less for culture, 74% less for sports, and 90% less for gender equality). It is the result of a completely irresponsible decision by the regional president Christelle Morançais for the 2025 budget. And the Pays de la Loire will face an additional 15 million euros in budget cuts for 2026.

You are part of the Mme Farceuse collective (Ms. Prankster), can you explain how and why this collective was formed? What are its current projects?

This collective was created in June 2022 when I was still in Nantes, with my friends Louise Chavanon and Eliot Broissand. We perform in various formations (from trio to quintet), which gives us a certain freedom in writing.

Right now, we’re taking our time; we’re not all based in the same cities, so it’s quite complicated to organize concerts/rehearsals.

We have done a few concerts and we plan to record an album and try out for showcases to be able to play as much as possible!

How would you describe the Vogelfrei quartet? What is your role in it?

Vogelfrei is a quartet with Loris Grillo, Anthony Jouravsky, and Antonio Barcelona.

“Vogelfrei” is the equivalent of “outlaw” in French: a person who breaks the laws, lives outside the laws, I think it describes our music well.

The group is led by Loris, but we all participate in the artistic direction. We will soon be recording an album with this group as well.

Is the duo Preset the most improvised of all your projects? What is its purpose?

Yes, it is the most improvised of all my projects, but it is not entirely so. With Antonio Barcelona, we work on textures, extended techniques, and different densities outside of improvisation, and then we improvise with these sound tools. Currently, we are exploring how to incorporate electronics into our performances to give them a new dimension and are increasingly leaning toward a show organized in multiple parts. Our focus is on analyzing the different aspects of the duo, how two entities communicate, can confront each other, intertwine, and elude each other…

You recently performed with Ailefroide and Ivresse, along with Fanny Ménégoz, in a wind trio with drums. This isn’t your only group without a harmonic instrument, is it an esthetic choice for you?

It was a very beautiful moment! I had never played an entire program in this formation, and I felt very comfortable; everyone was exactly where they needed to be. And I was very grateful to play Fanny’s compositions!

Indeed, this is not the only project without a harmonic instrument that I play in.

I love the sound of these formations; there is something deep and dry that attracts me.

On the other hand, I have discovered a certain fondness for the counterpoint created by the voices of monodic instruments (between them and with the drums), and moreover, the absence of instruments that mark the harmony allows our ear to be less influenced when improvising in a tonal or modal context. We are therefore freer!

Do you still play the violin on stage, and if so, what are the differences in playing, improvisation, and expression between these two instruments?

Yes, more specifically, I started playing the violin on stage again; I had stopped for a few years. Apart from the different timbres when playing the trumpet and violin conventionally, I don’t make any distinctions between the two instruments in my improvisation style; I think in the same way. On the other hand, working with sounds using extended techniques allows me to create a bridge between the sounds I produce.

In general, the younger generations of musicians who graduate from the conservatory form bands. What is your band?

My band is called Mouvances (and it gives its name to the first album). I asked people I admire a lot to play with me: Vladimir Sekula on piano, Tom Boizot on double bass, and Antonio Barcelona on drums. Sometimes we invite Lou Ferrand, a singer who, in my opinion, has a very deep and touching understanding of music.

The #IWD project is a European initiative to give visibility to female musicians. We must continue to insist. What is your position as a female musician on the subject?

I am in favor of this kind of initiative, as long as it doesn’t divert attention from the organization that highlights the musician. Because sometimes these initiatives end up being pure pinkwashing, and that’s a bad thing.

We must continue to insist on including women and gender minorities, because it is only thru radical actions that we achieve results: better visibility, more women and gender minorities in orchestras/groups, etc…

The new generation seems much more sensitive to issues of gender, equality, and representation. Are you still confronted with sexist, discriminatory, or simply inappropriate attitudes?

Yes, the new generation is more sensitive to these issues. And obviously, like everyone, I am confronted with sexist attitudes. Certainly, progress has been made, but there is still a hostile climate for women. The world of jazz is not a bubble excluded from our sexist and patriarchal society, and there is still a lot of fundamental work to be done to change that.

Where can we hear you (album, website, concerts)?

The first album by Mouvances has been released on all platforms under the label l’Autre Records. I sometimes post concert recordings on my Soundcloud.

Regarding my upcoming dates, I post them on my Instagram account, and I think I’ll create a website soon to gather everything.

Este artículo se publica simultáneamente en las siguientes revistas europeas, en el marco de “Milestones”, una operación para destacar a las jóvenes músicas de jazz y blues : Citizen Jazz (FR), JazzMania (BE), Jazz’halo (BE), Meloport (UA), UK Jazz News (UK), Jazz-Fun (DE), In&Out Jazz (ES) y Donos Kulturalny (PL).

This article is co-published simultaneously in the following European magazines, as part of « Milestones » an operation to highlight young jazz and blues female musicians : Citizen Jazz (FR), JazzMania (BE), Jazz’halo (BE), Meloport (UA), UK Jazz News (UK), Jazz-Fun (DE), In&Out Jazz (ES) and Donos Kulturalny (PL).

#Womentothefore #IWD2026