Café El Despertar Jazz Club – Carolina Ruiz Interview

Café El Despertar

Jazz Club

Carolina Ruiz

Interview

Resistir desde el jazz: El Despertar cumple 45 años como refugio musical en Madrid

En una esquina discreta del barrio de Lavapiés, en Madrid, mientras un contrabajo se afina y las onversaciones se cruzan entre mesas pequeñas y luces cálidas, el jazz sigue respirando con naturalidad. El Café El Despertar no es solo un club: es un refugio cultural, un punto de encuentro y una memoria viva de la ciudad. En un Madrid donde los espacios dedicados a la música en directo luchan por sobrevivir y donde el cierre de locales históricos ha dejado una herida profunda en la escena, cumplir 45 años es mucho más que una efeméride: es un acto de resistencia.

Fundado en 1981, en plena Transición, El Despertar nació como un proyecto cultural íntimamente ligado al jazz, a la tertulia, al pensamiento crítico y al encuentro humano. Cuatro décadas después, ese espíritu sigue intacto, aunque el contexto sea más complejo que nunca. Mantener viva la llama del jazz en Madrid exige hoy convicción, trabajo constante y una enorme dosis de amor por la música y por quienes la hacen posible.

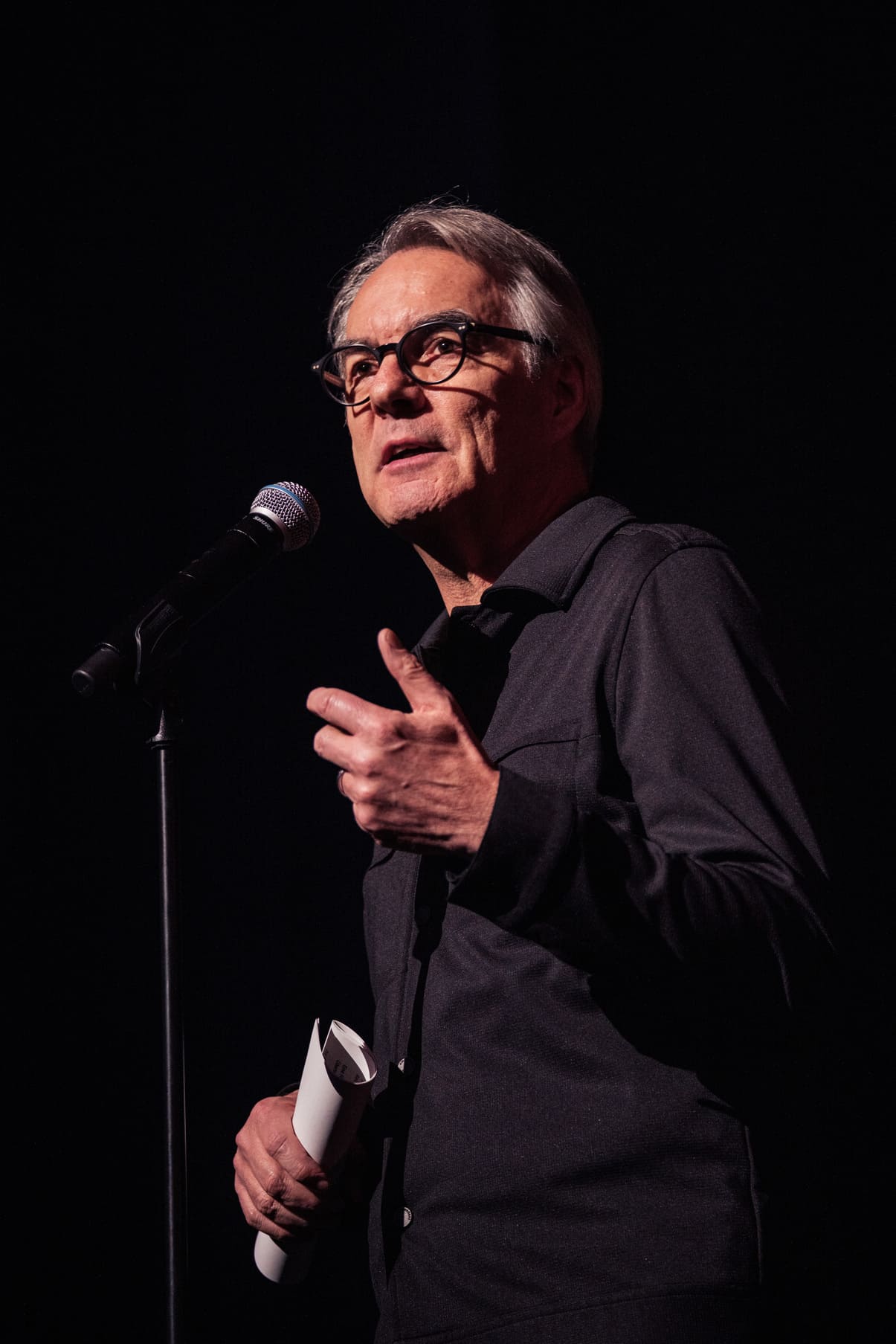

Al frente de esta nueva etapa se encuentra Carolina Ruiz, hija de los fundadores, que asumió la gestión del local en un momento especialmente delicado, justo antes de la pandemia. Con una mirada que combina memoria, sensibilidad y compromiso, Carolina ha sabido recoger el legado familiar y transformarlo en una programación viva, diversa y profundamente conectada con la escena local y nacional. Bajo su dirección, El Despertar sigue siendo un espacio donde conviven generaciones de músicos, donde el público joven descubre por primera vez la emoción de un concierto de jazz en directo y donde la comunidad se construye noche tras noche.

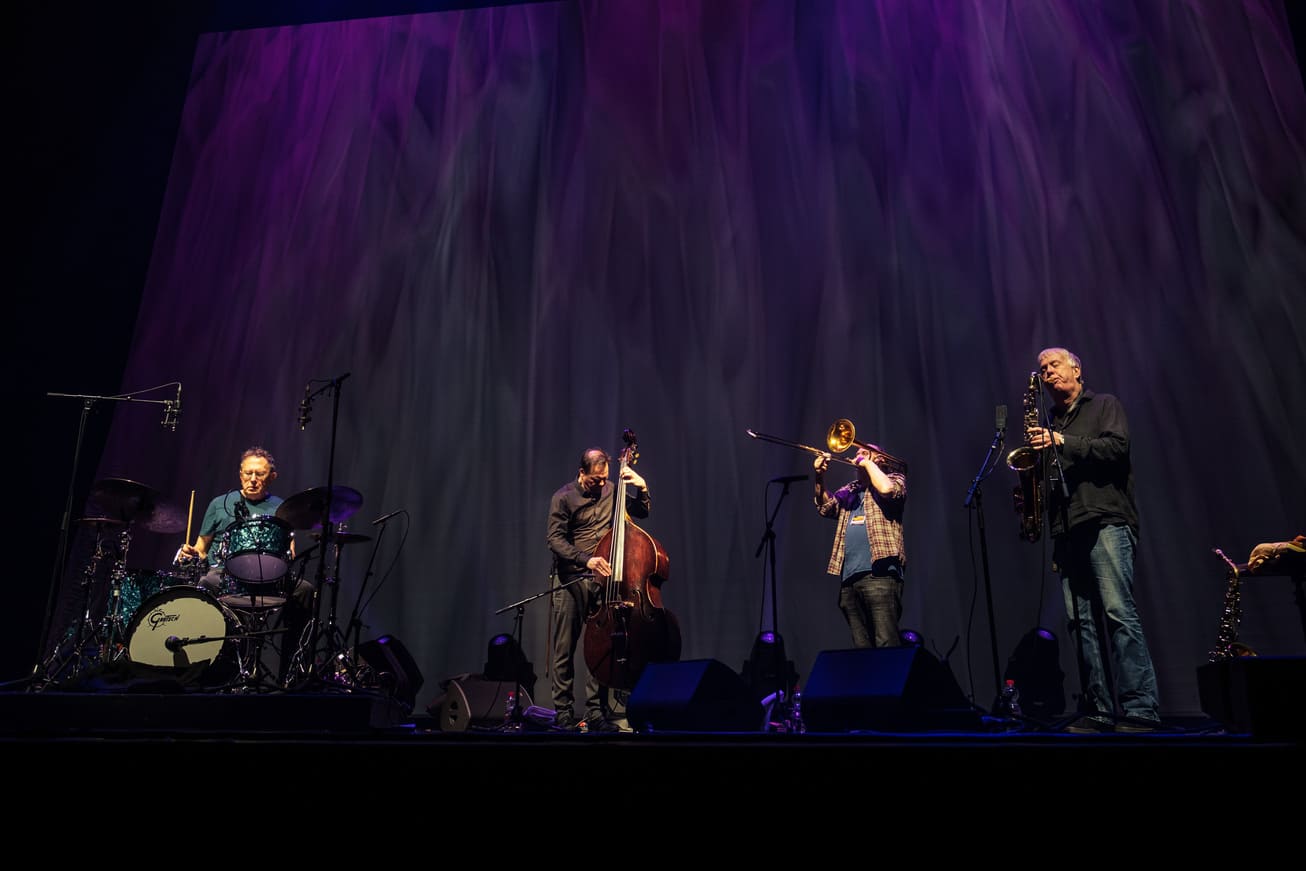

La entrevista tuvo lugar entre la prueba de sonido de un concierto y el bullicio propio de un local en plena actividad. El rumor de las conversaciones, el roce de los instrumentos, el ir y venir de músicos y camareros acompañaron una charla sincera y cargada de emoción. Un ambiente en movimiento que refleja exactamente lo que es El Despertar: un lugar que invita, que llama y que propone vivir la música de cerca, sin artificios, en contacto directo con quienes la crean.

In&Out Jazz Magazine: Gracias por recibirnos Carolina. Sabemos el ajetreo que supone hacer este parón. Estamos aquí por un motivo especial: los 45 años del Café El Despertar, todo un hito que además ha sido reconocido por distintas instituciones. De hecho, este año habéis recibido el Premio Jazz con Sabor a Club de Madrid en Vivo.

Tú llevas al frente de El Despertar desde la pandemia. ¿Qué emociones te recorren al pensar en la trayectoria del local? ¿Y qué supone para ti darle continuidad en el futuro a un espacio tan querido?

Carolina Ruiz: ¡Qué pregunta más bonita! Pues muchísimas emociones, me costaría resumirlas. Empecé justo antes de la pandemia, en un momento muy delicado a nivel personal porque a mi padre le detectaron un cáncer —afortunadamente se pudo atajar a tiempo— y enseguida llegó todo lo demás.

El Despertar para mí es hogar y familia. La música ha estado siempre presente en mi vida, no conozco un momento sin jazz, y sin jazz en vivo. Desde pequeña he escuchado discos en casa, he visto a mi padre cantar canciones montañesas —él es cántabro—, he vivido la música como algo cotidiano.

Venir aquí con él, sentarnos en silencio a escuchar, observar a los músicos y a las personas… todo eso forma parte de mi memoria. Es una mezcla muy profunda de familia, descubrimiento del mundo, de las personas y de sus singularidades. También hay un deseo muy fuerte de conservar el pasado, integrándolo con el presente, que es enorme.

In&Out Jazz Magazine: Tus padres abrieron el Despertar en 1981. ¿Cuáles fueron sus motivos para crear un lugar así? ¿Fue una decisión puramente musical o había también una voluntad cultural y social?

Carolina Ruiz: Es un relato que he ido recibiendo desde siempre, casi de forma oral. Sé que el impulso inicial fue de mi padre. Durante la pandemia me dediqué a ordenar papeles, proyectos, libros, discos, cintas, vinilos… y ahí encontré su historia de una forma casi arqueológica.

El nombre “El Despertar” tiene mucho sentido. Fue su despertar personal. Mi padre era ingeniero, daba clases en la Politécnica, venía de una familia trabajadora y había alcanzado una posición estable. Pero con la muerte de Franco y la Transición, empezó a sentir inquietudes muy fuertes relacionadas con la cultura, la música, las humanidades y la política.

Conoció a restauradores, empezó a imaginar un proyecto cultural ligado al jazz, al encuentro, a la tertulia. Compró este local, que antes era una tienda de ultramarinos, y construyó un espacio inspirado en los cafés de tertulia de finales del XIX y principios del XX, con la música en vivo como eje central. Todo lo que se ve aquí es una puesta en escena pensada al detalle.

Cumplir 45 años hoy es casi un acto de resistencia, más aún con el cierre de espacios históricos como el Café Central. ¿Cómo se vive esa resistencia?

La resistencia está en el origen. Mi padre siempre me explicó que montó el Despertar porque era huérfano, porque no tenía una oposición familiar que le frenara. Tomar la decisión de abrir un club de jazz no tiene que ver con el capital económico, sino con una convicción profunda, con una necesidad vital.

Eso sigue siendo así. Es una mezcla de pasión y necesidad personal de riqueza interior. Esa riqueza es la que te da fuerzas para resistir. Además, no es una resistencia individual: es una sinergia entre quienes programamos, los músicos y el público. Se crea una comunidad, que era exactamente el propósito original del Despertar.

¿Cómo describirías al público que viene hoy al Despertar? ¿Qué tipo de oyentes sentís que os acompañan y qué buscas que se lleven después de cada concierto?

Algo que me sigue sorprendiendo muchísimo es la cantidad de público joven. Jóvenes que, en muchos casos, se encuentran aquí por primera vez con un concierto de jazz en vivo. Muchos salen muy emocionados, muy agradecidos por la experiencia.

Eso es precioso, porque demuestra que la música en vivo sigue teniendo un poder enorme. Me gusta pensar que se llevan una vivencia real, una conexión directa con los músicos, con el espacio y con ellos mismos. Si salen con curiosidad, con ganas de volver a escuchar música en directo, ya hemos hecho algo importante.

La programación es muy intensa, prácticamente continua. ¿Qué criterios utilizas para seleccionar a los músicos?

Aprendí el oficio viendo a mi padre programar. Tenía un cuaderno —que ahora yo he replicado— y hablaba directamente con los músicos. Sus criterios tenían que ver con el talento local, con su gusto personal y con la complicidad humana.

Hoy el criterio sigue siendo muy parecido: calidad musical y calidad humana. Tiene que haber química y comprensión del proyecto. Hay tantísimos músicos de gran nivel que no doy abasto. Debería haber muchos más clubes de jazz como este en Madrid.

Aquí confluyen generaciones: músicos que venían con mi padre, los de mi generación y otros mucho más jóvenes. También llegan artistas de fuera, a través de giras y de redes. Todo eso crea una red muy viva.

En El Despertar hacemos jazz cuatro días a la semana, diez meses al año, porque existe una escena local y nacional riquísima, muy activa y en constante crecimiento.

Para terminar, ¿cuándo se cumplen exactamente los 45 años y si tenéis pensado celebrarlo?

Fue en primavera de 1981, así que la celebración real será en 2026. Me encantaría poder hacer una buena celebración, con una programación especial. El espacio es pequeño, así que veremos si puede ser en uno o dos días, pero ojalá tenga la energía y la organización para hacerlo como se merece.

Muchísimas gracias, Carolina. Volveremos en primavera.

Gracias a vosotros. Esta siempre será vuestra casa.

Escrito por Pedro Andrade

22 de enero de 2026