Ornella Noulet – A Journey With Ola Tunji

.

.

.

.

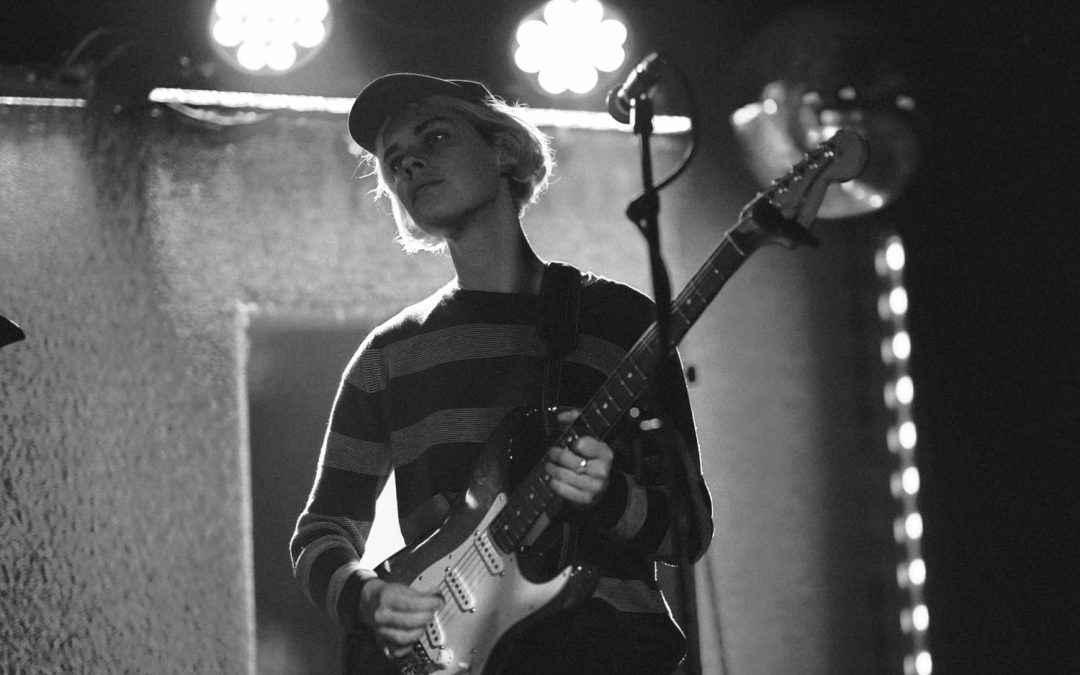

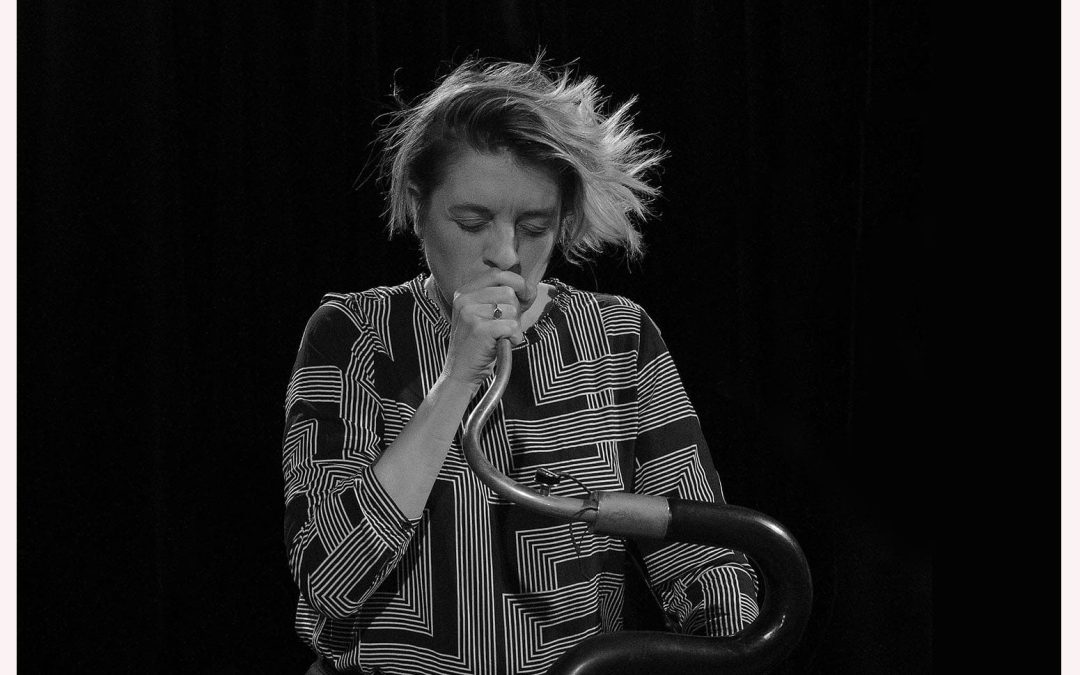

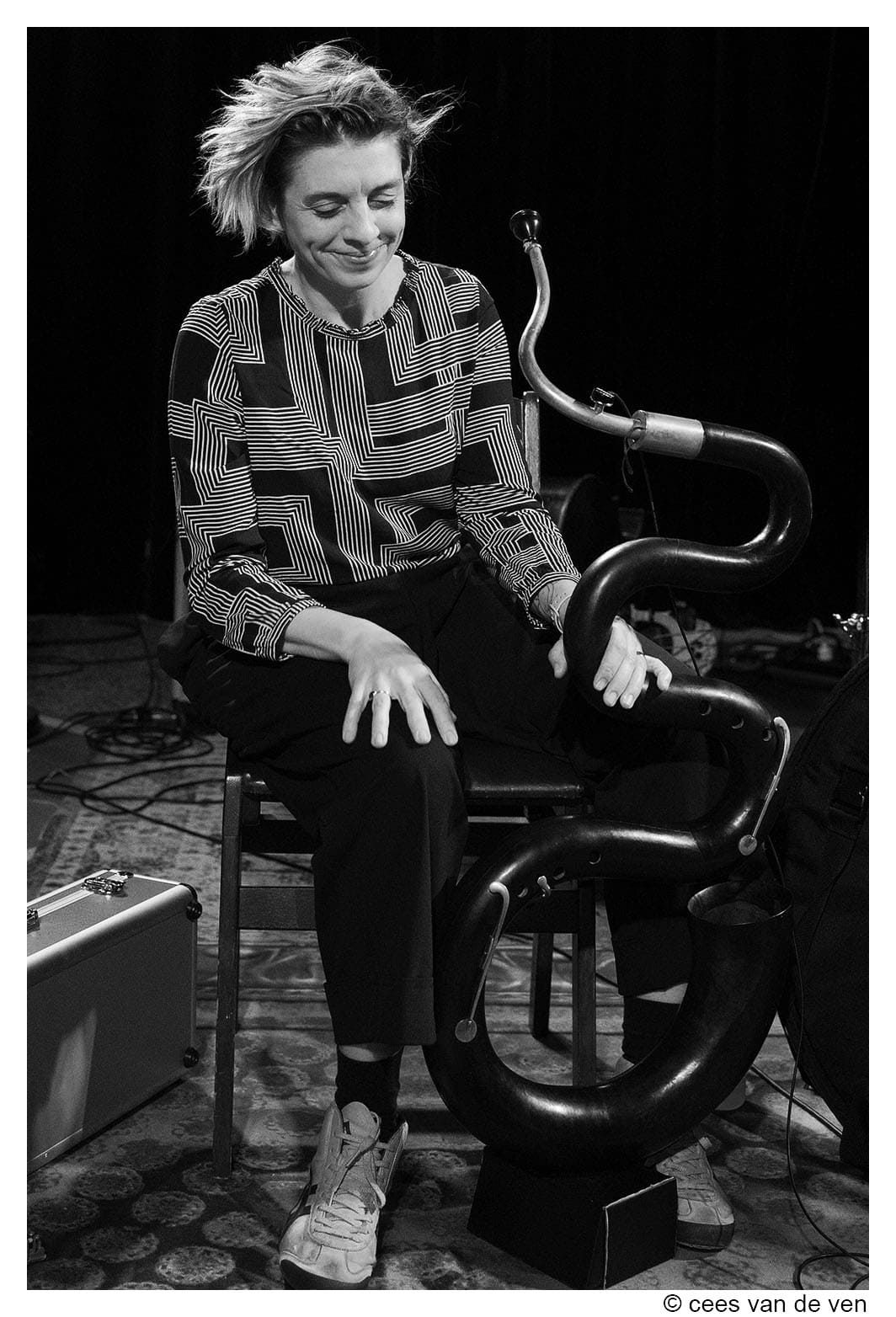

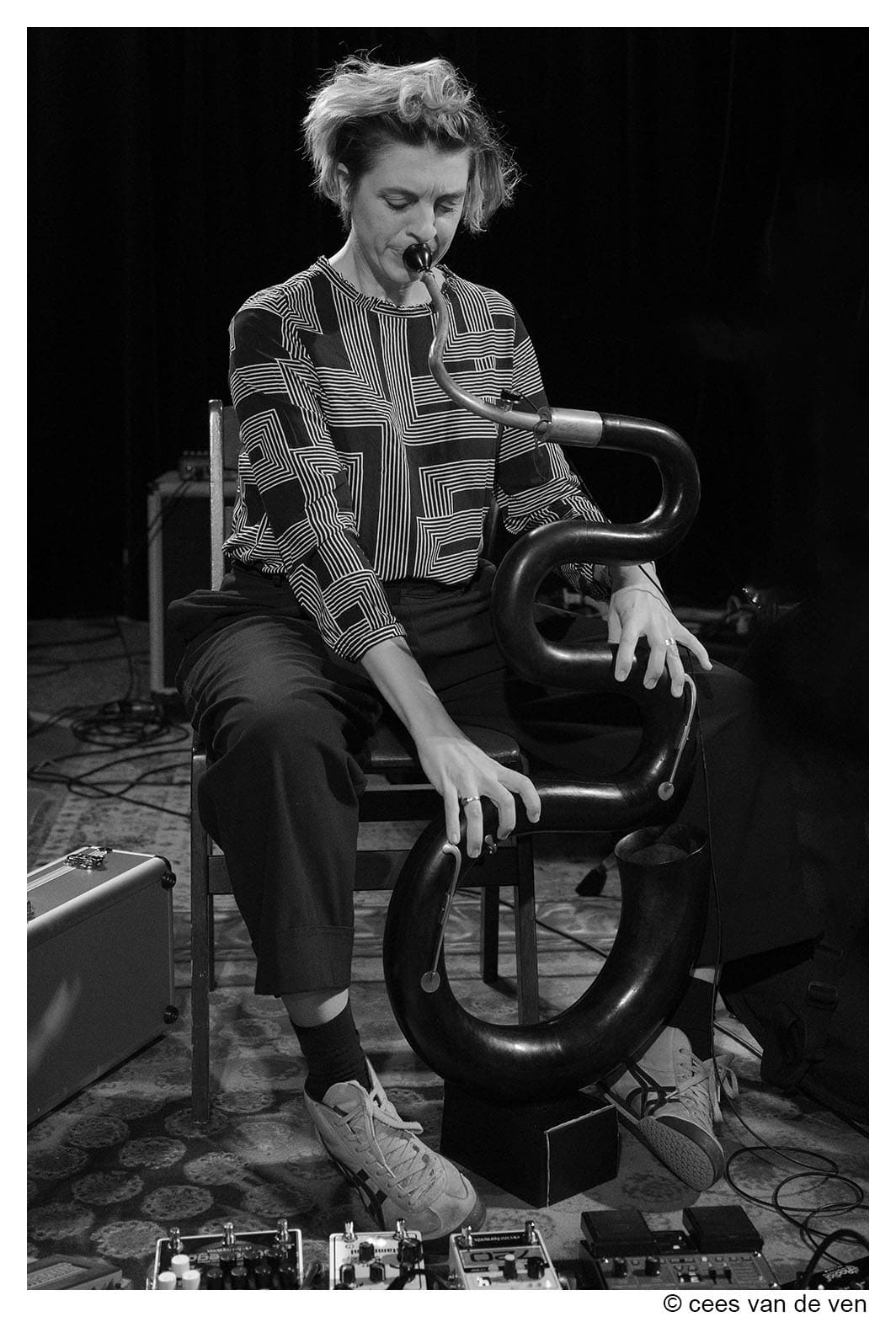

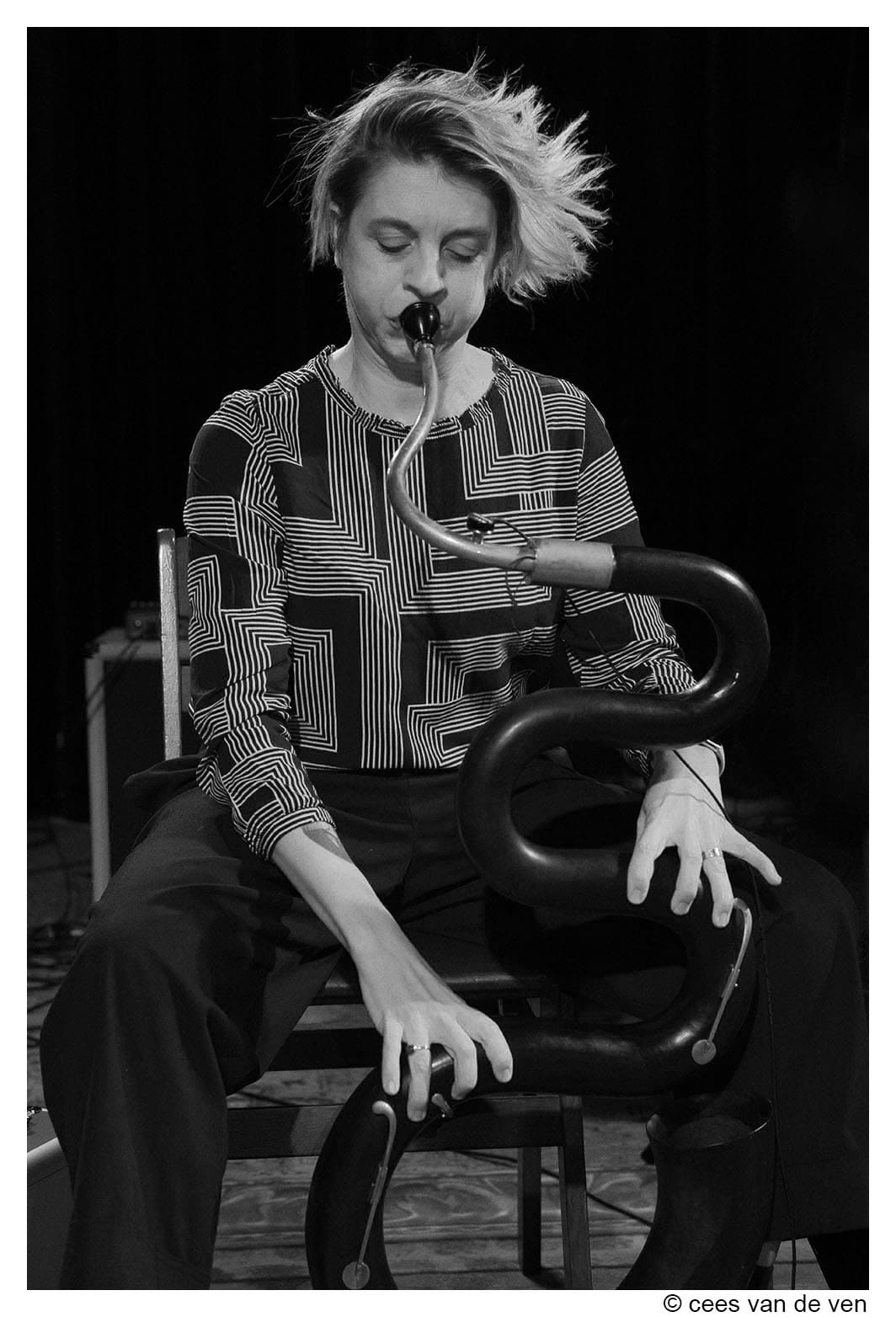

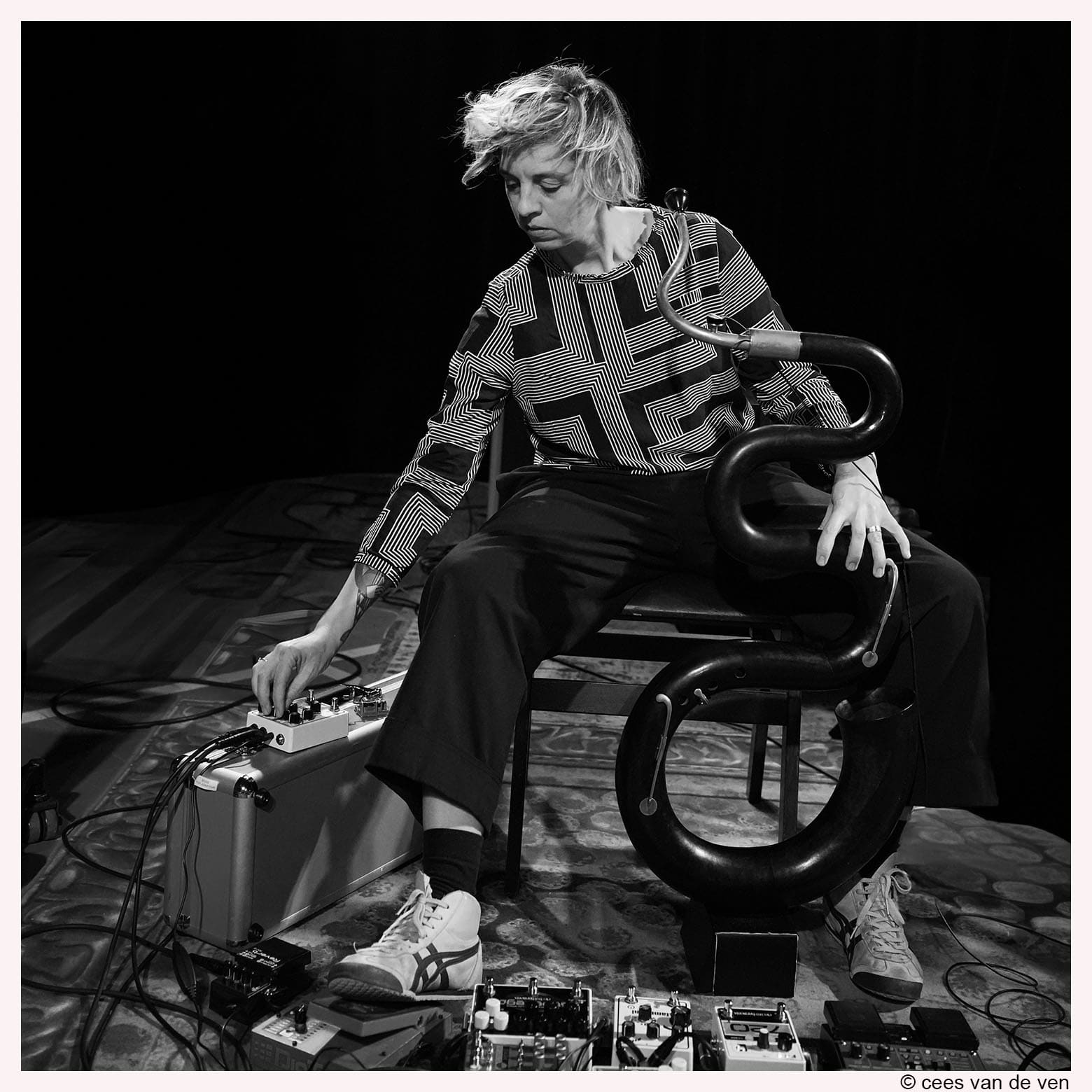

Ornella Noulet

A Journey With Ola Tunji

09

March, 2026

By: Yves Tassin

Photos: © France Paquay

Traduction : Alain Graff

Jazzmania/ #IWD2026 | WomenToTheForce | A Journey With Ola Tunji

A Journey With Ola Tunji

The band Ola Tunji, and particularly its saxophonist Ornella Noulet, have been attracting the attention of jazz fans in recent months, which has sparked the interest of the W.E.R.F. label and piqued our curiosity.

We don’t know much about you yet, but that could soon change. Could you introduce yourself and tell us about your background and musical experience?

Ornella Noulet: I am French and grew up in the suburbs of Paris. I am twenty-four years old. I started playing the saxophone at the age of seven at the Conservatoire des Lilas. Before that, I had taken music lessons and tried several instruments, but the saxophone clearly stood out. At the age of seventeen, I entered the Paris Conservatoire where I studied with Pascal Gaubert. Then, I joined the regional conservatoire and attended Jean-Charles Richard’s classes. Finally, I took and passed the entrance exam for the Royal Conservatoire of Brussels. I am currently studying with Jeroen Van Herzeele.

Many French musicians studied at the Royal Conservatoire of Brussels. How do you explain this?

Yes, actually, we ́re getting a very good feedback in France. Brussels is a very culturally rich city. Besides, there’s also a question of mentality. Belgians are more ‘open’ in terms of culture than the French. Brussels is also a very cosmopolitan place, which attracts a lot of people and influences the music that’s played there.

Do you mean in learning methods ?

Indeed, but also in terms of aesthetics. Once again, I find the Belgian scene more open than the French scene… I’m going to make some enemies! (laughs) But that’s what I think.

What were your first musical experiences ? I find it a bit difficult to imagine the journey, or more precisely, the path that a young girl or a young musician takes to get to Coltrane. And why Coltrane in particular ?

Well, as often, my first musical experiences came from my family. My father listens almost exclusively to African-American music. Since I was very young, I have heard a lot of gospel, soul, funk… especially from the 1970s. I guess that must have had a big influence on my musical tastes. I also took dance lessons. In fact, I used to associate what my father listened to with body movements. I didn’t discover jazz until I was fourteen. Before that, I didn’t know what it was. And I can tell you that I didn’t like it at first ! In fact, it took me a year to begin to understand how it worked. Until then, I had no tools to do it. I felt a bit lost with my saxophone…

I discovered Coltrane with his album “Ballads”. Here again, I didn’t immediately connect with it. I really liked the sound of his saxophone, but I didn’t understand his vocabulary or phrasing. I didn’t have the intellectual understanding necessary to appreciate it. I think that’s the case for many young musicians. Coltrane’s music seems elusive when you’re a teenager.

I got back into jazz when I arrived in Brussels and met the people who became my friends and with whom we formed Ola Tunji. But this new contact with jazz came about in a different way, through a more spiritual journey. So yes, I eventually felt a deep attachment to jazz. I identified with it emotionally. From that moment on, I sought to better understand this music, to study it and to educate myself.

Does it mean that all the members of the Ola Tunji quartet are into Coltrane? Do they have other interests?

Yes, we are fans of Coltrane. But keep in mind that what is also unique about Coltrane is that his music paves the way for others. It is a mistake to believe that there is such a thing as Coltrane sectarianism. On the contrary, it is a whole! Everything is there, everything has its purpose …

There is openness, but also work to be done, isn’t there?

Absolutely, you can’t reach that level without a tremendous amount of work and discipline.

Could you remind us where the reference to “Ola Tunji” comes from ?

Well, actually, it’s the name of Coltrane’s last live recording. It’s named after the last club he played in. In fact, it’s a cultural centre in New York, which itself takes its name from the Nigerian percussionist Babatunde Olatunji.

I feel that the past year has been crucial for your career. Have you realised that you are now going to pursue a career as a musician?

The desire to make a living from music has been with me since I was seventeen. I came to Brussels to become a professional musician, that’s for sure.

In fact, over the past year, I have mainly gained confidence in myself. I now dare to think that I am capable of achieving this. (smile)

Your band Ola Tunji has made a name for itself, particularly in Flanders, where you have been invited to participate in major festivals (Ghent and Bruges).

As a matter of fact, Ghent was a springboard and a very divisive moment for the band as well. In 2024 we released an EP, which we sent to Benny Claeysier, the boss of the W.E.R.F. label. He really appreciated it and it enabled us to get things organised, in particular to register for this springboard, which helped us to make ourselves known.

You received an award there, didn’t you ?

Yes, we received the audience award and the jury award, which helps us a lot and gives us the means to record at W.E.R.F. Our EP will be released in April on vinyl, then we will enter the studio to record an album that should be released in October. These awards have done us a world of good. And the feeling that we can touch people with our music is so powerful !

…

Tonight you will be playing in a duo with Egon Wolfson, Ola Tunji’s drummer (the interview was recorded in January in Liège, at the Cercle du Laveu). Does it mean we can expect more in improvisation or free jazz?

I love free jazz. This music is also an integral part of Coltrane’s music. He is one of its innovators, if not one of its creators. The history of free jazz is immense and there is so much to discover and study.

Of course, its legacy is very important in terms of art, in terms of what this music has contributed to other musical genres.

Besides, there is also a political dimension that I am committed to. There is such a liberating force in free jazz, an opposition to fascism. I am a woman and I come from the suburbs, from a working-class family. I feel very involved in the fight against oppression and in the struggle to safeguard our rights. I believe that I too have a role to play in this.

Can you tell us about your personal experience as a young woman working in the jazz world?

There is so much I wish to express, and I think it’s important. With the recognition I enjoy today, I can say that things are getting better. But I still get inappropriate comments at the end of a concert, for instance about my playing or my appearance. In any case, the kind of comments that no one would dare make to a man.

And comments about the way you dress, perhaps ?

Yes. Comments are flying thick and fast if I wear a skirt. So much so that at one point, I tended to dress more like a man. On stage, for example, I wear more loose-fitting clothes so that my figure isn’t visible and I also wear very little make-up.

And, at one time, I even neglected myself a little, in a way, to blend in with the other musicians. I wanted to be seen like the others, who were mostly male musicians.

The jazz world is also about jams… How do people view a young girl who turns up with her saxophone?

Well, I can tell you that I have had some very bad experiences, particularly in Paris. Starting out as a young woman is very difficult and cruel at times… In fact, you feel alone and you don’t identify with many people. Sometimes you even feel unsafe. Maybe the worst part of it all is the feeling of not belonging, which I experienced for so many years.

So you had to hang in there…

Yes. I also had to rebel against institutions, against teachers from another time and from other generations. This ends up costing us energy, which we expend more than men.

You’re telling me that things are getting a bit better now. We can see that other young female musicians are appearing on the Belgian jazz scene, such as Alejandra Borzik, Adèle Viret and others. Do you discuss this sensitive subject together ?

Yes, of course. We’re building up a real community, which is very useful. There is a great deal of solidarity among us and we support each other. I have high hopes for this generation and for our generation, ultimately.

What are your wishes for 2026 ?

Well, I would like to be at peace with what I do. I also wish to share pleasant moments with my friends and see my family. And above all, I want to continue to love music just as much as I do now. But I have no doubt about that! (smile)

Este artículo se publica simultáneamente en las siguientes revistas europeas, en el marco de “Milestones”, una operación para destacar a las jóvenes músicas de jazz y blues : Citizen Jazz (FR), JazzMania (BE), Jazz’halo (BE), Meloport (UA), UK Jazz News (UK), Jazz-Fun (DE), In&Out Jazz (ES) y Donos Kulturalny (PL).

This article is co-published simultaneously in the following European magazines, as part of « Milestones » an operation to highlight young jazz and blues female musicians : Citizen Jazz (FR), JazzMania (BE), Jazz’halo (BE), Meloport (UA), UK Jazz News (UK), Jazz-Fun (DE), In&Out Jazz (ES) and Donos Kulturalny (PL).

#Womentothefore #IWD2026