Petros Klampanis Interview – Jazz Círculo – Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid

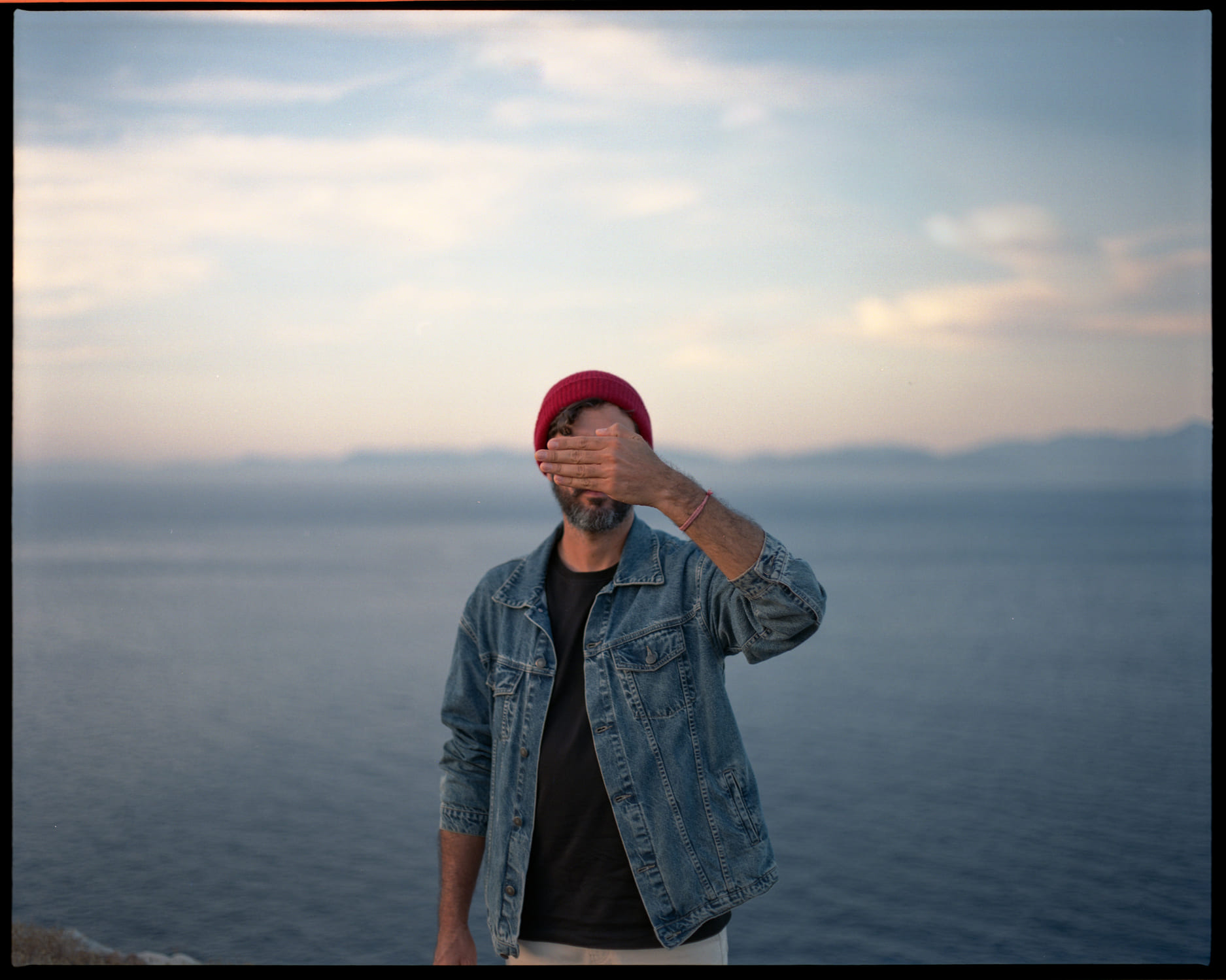

Petros Klampanis

Jazz Círculo

Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid

Interview

ESCUCHAR LO QUE SUCEDE DEBAJO DE LA SUPERFICIE

Contrabajista, compositor y productor, Petros Klampanis se ha consolidado como una de las voces más personales y reflexivas del jazz contemporáneo europeo. Con una trayectoria marcada por la profundidad sonora, la atención al detalle y una relación orgánica entre composición e improvisación, Klampanis ha construido un lenguaje musical que dialoga con la memoria, el silencio y el espacio.

Su último trabajo, Latent Info, nominado por la Academia Alemana en la categoría de World Music, es un ejemplo claro de esta búsqueda: una música que se revela poco a poco. El próximo 27 de febrero, Klampanis presentará este proyecto en Madrid, en el Círculo de Bellas Artes, dentro del ciclo Jazz Círculo, acompañado por Kristjan Randalu y Ziv Ravitz.

Con motivo de esta cita, In&Out Jazz Magazine conversa con Petros Klampanis sobre el origen de Latent Info, su manera de entender el directo, su vínculo con España y su visión del presente y futuro de su música.

In&Out Jazz Magazine: ¿Cómo surgió Latent Info y qué puede esperar el público en directo en Madrid?

Petros Klampanis: Latent Info nació de la necesidad de trabajar con menos información en la superficie y con más confianza en lo que sucede por debajo. Me interesaba qué ocurre cuando se deja más espacio, cuando las cosas se sugieren en lugar de afirmarse. El material se fue construyendo poco a poco, a través de la escritura, los ensayos y la escucha.

En directo, la música es abierta y reactiva. El público puede esperar una actuación que valora la dinámica, el silencio y la sorpresa. No se trata de reproducir el disco, sino de permitir que la música tome forma en la sala, en tiempo real.

Latent Info es ya tu undécimo álbum, y detrás de él hay un largo recorrido como compositor, intérprete y líder de banda. Desde 2020, además, diriges tu propio sello discográfico, PKmusik, produces a otros músicos y lideras proyectos en distintos formatos. ¿Cómo consigues compaginar todos estos roles? ¿Cuál de ellos ocupa actualmente la mayor parte de tu tiempo y energía? ¿Cómo mantienes el equilibrio entre todos?

No están tan separados como podría parecer. Componer, tocar, producir y llevar un sello parten del mismo lugar: escuchar con atención, tomar decisiones claras y compartir la música. El desafío es principalmente práctico, en términos de tiempo, concentración y energía.

Ahora mismo, la mayor parte de mi energía está centrada en mi propia música y en dar forma a los proyectos para que puedan existir de manera coherente a lo largo del tiempo. PKmusik me permite extender esa forma de pensar a otros artistas, pero intento mantener una escala humana para que no se coma la parte creativa.

Tus dos primeros discos forman parte del catálogo de Inner Circle, el sello dirigido por Greg Osby, una figura clave del jazz contemporáneo. Sabemos que vuestra relación va más allá del ámbito discográfico y que habéis compartido escenario en numerosas ocasiones. ¿Podrías hablarnos de esa conexión y de lo que ha significado trabajar con Greg Osby, tanto a nivel musical como personal?

Mi relación con Greg siempre se ha basado en la confianza y el respeto mutuo. Inner Circle fue un entorno muy importante para mí al principio, porque fomentaba la responsabilidad artística y la independencia. Trabajar con Greg me ayudó a entender el valor de la claridad, de saber por qué haces algo y respaldarlo plenamente.

Para el concierto de Madrid estarás acompañado por un trío muy especial, con Kristjan Randalu al piano y Ziv Ravitz a la batería. ¿Qué te une a ellos y qué tipo de conversación musical se genera dentro de este trío?

Con Kristjan y Ziv compartimos una misma percepción del tiempo, el espacio y la proporción. No nos interesa llenar cada momento, sino dejar que la música respire. La conversación es muy fluida y se basa más en la reacción y la escucha que en roles predeterminados.

También hay un fuerte sentido de confianza, y eso nos permite asumir riesgos sin forzar nada.

A lo largo de los años has construido una relación muy sólida con músicos de España, colaborando con artistas como Viktorija Pilatovic o Antonio Lizana, entre otros. ¿Qué encuentras en la escena musical española que conecta de manera tan directa con tu forma de entender y hacer música? ¿Cómo ves el panorama actual del jazz en España desde tu perspectiva?

Lo que valoro de la escena musical española es el equilibrio entre tradición y apertura. Hay un fuerte sentido de identidad, pero también una gran disposición a experimentar y a difuminar fronteras. Eso conecta mucho con la forma en que yo mismo entiendo la música.

Desde mi punto de vista, es una escena vibrante y diversa, con músicos profundamente conectados con su sonido, pero no limitados por etiquetas.

Latent Info ha sido nominado en la categoría de World Music por los premios de la Academia Alemana. El título sugiere la experiencia de una realidad efímera que existe, pero que no siempre es visible. ¿Qué tipo de material emocional, cultural o sonoro querías sacar a la superficie con este proyecto?

El título hace referencia a cosas que existen pero que no siempre son visibles de inmediato, a nivel emocional, cultural o sonoro, y que aun así dan forma a nuestra realidad. No me interesaba tanto hacer una declaración como crear las condiciones para que ciertos sentimientos o recuerdos pudieran emerger de manera natural.

Tiene que ver con desplazamientos sutiles, movimientos internos y con ese tipo de información que se revela poco a poco, si se le da tiempo.

Nueva York ha sido una ciudad clave en tu trayectoria, y acabas de regresar de un viaje allí. ¿Qué ha significado para ti, tanto a nivel personal como artístico, haber vivido durante tanto tiempo y haber compartido tantas experiencias musicales en Nueva York?

Nueva York ha sido un lugar de aprendizaje intenso y de fricción. Me desafía constantemente, tanto musical como personalmente. Vivir allí moldeó mi forma de escuchar, de trabajar y de relacionarme con otros músicos.

Ahora, aunque no viva allí a tiempo completo, sigue siendo un punto de referencia muy importante. Es una parte esencial de mi música y continúa influyendo en mi trabajo de muchas maneras.

Como comentamos previamente. En 2020 fundaste tu propio sello independiente, PKmusik. ¿Qué te llevó a dar ese paso en ese momento concreto y qué valores buscas proteger y transmitir a través del sello? ¿Qué artistas han publicado su música en PKmusik?

Fundé PKmusik en 2020, en un momento en el que sentí que era importante crear una estructura alineada con mis valores. El objetivo era apoyar música que necesita tiempo, cuidado y contexto, sin la presión de obtener resultados rápidos.

El sello se centra en proyectos impulsados por los propios artistas y en relaciones a largo plazo. El catálogo incluye artistas como Viktorija Pilatovic, Daniel Juarez, Quique Ramirez, Elana Sasson y otros cuyo trabajo respeto profundamente.

Después de Latent Info y de este concierto en Madrid, ¿en qué estás trabajando actualmente y qué podemos esperar de tus próximos pasos artísticos?

Actualmente estoy trabajando en nueva música que continúa algunas de las preguntas abiertas por Latent Info, pero desde otro ángulo. También estoy desarrollando varios proyectos colaborativos, produciendo discos y dedicando tiempo a convertirme en un mejor músico.

Para mí, los próximos pasos tienen menos que ver con la expansión y más con la depuración.

Una vez más, muchas gracias por tu tiempo, tu disponibilidad y tu amabilidad. Es un verdadero placer poder contar contigo y con tu música.

Igualmente, gracias a vosotros